Bias

Elena Dudukina

Objective of epidemiologic research

“To obtain a valid, precise, and generalizable estimate of the effect of an exposure on the occurrence of an outcome (e.g., disease)”

- Design → enhance the precision and validity of the effect estimate

- No study is perfect

- Interpret the precision and validity of the effect estimate

T. Lash, M. Fox. Applying Quantitative Bias Analysis to Epidemiologic Data

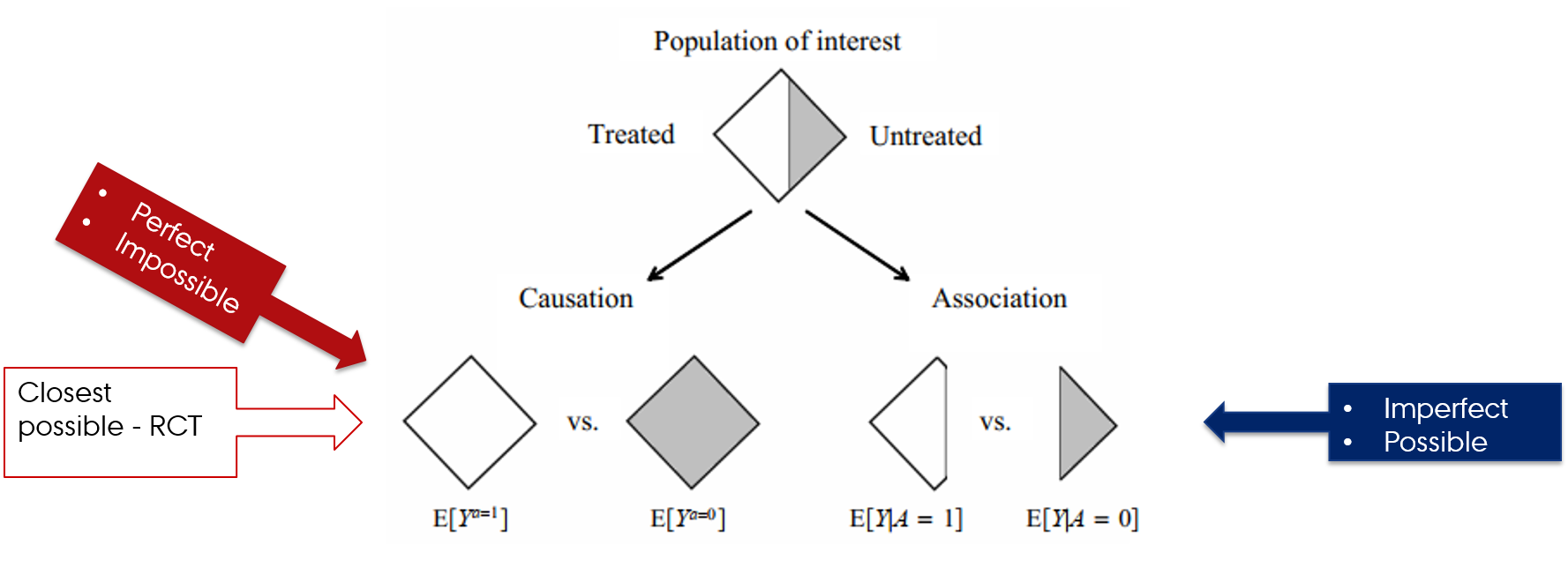

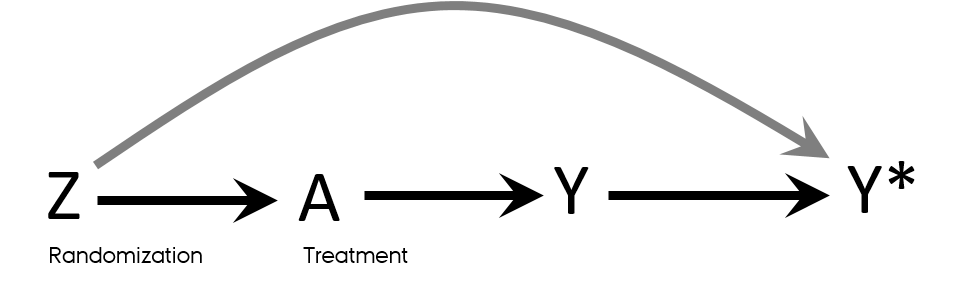

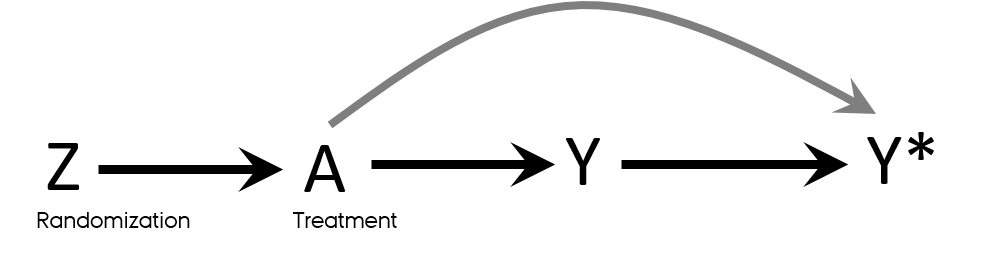

Counterfactual vs factual worlds

- Counterfactual comparisons of exposed and unexposed → perfect and impossible

- RCTs → closest we can get to the counterfactual comparison of exposed and unexposed

Hernán MA, Robins JM (2020). Causal Inference: What If. Boca Raton: Chapman & Hall/CRC.

Estimating magnitude of effect in epidemiologic studies

- Design

- Data

- Statistical analyses

Error in epidemiologic research

- Random error

- Sampling (random) variability

- Chance

- Systematic error (bias)

- Selection bias

- Confounding

- Measurement (information) bias

Validity

- No bias

- Valid study = Study with minimal bias (systematic error)

- Internal validity

- The validity of the inferences about the source population

- External validity

- Generalizability

- Validity of the inferences about people outside source population

- Internal validity → external validity

Accuracy

- Value of the parameter is estimated with little error

- Errors in estimation: random or systematic

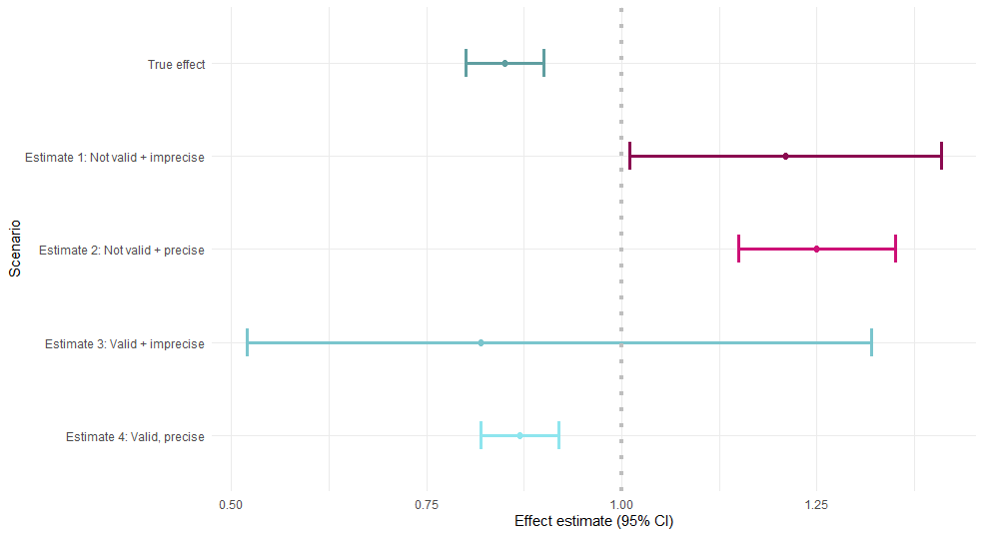

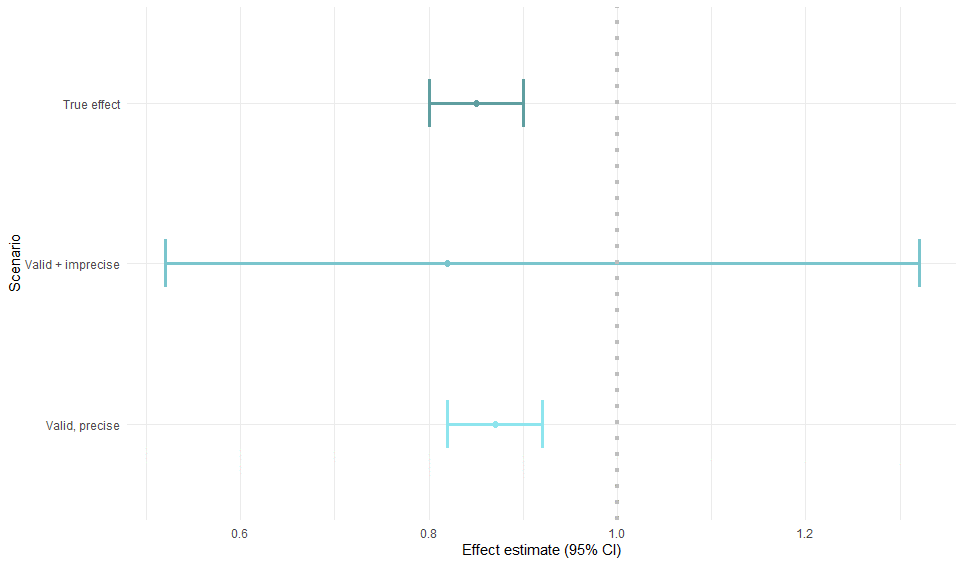

Had we known the true effect of the exposure on the outcome (simulation):

Random error

- Can chance be solely responsible for an observed association?

- Reducing random error → increasing precision of an estimate

- Enlarging the size of the study

- “The statistical dictum that there is no sampling error if an entire population (as opposed to a sample of it) is studied does not apply to epidemiologic studies, even if an entire population is included in the study”

- Planning study size based on desired precision of an estimate

- Envision stratification analyses

Rothman KJ, Greenland S. Planning Study Size Based on Precision Rather than Power. Epidemiology. 2018.

Precision

- No random error

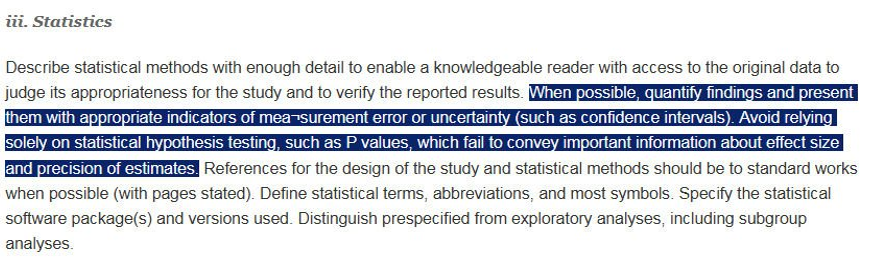

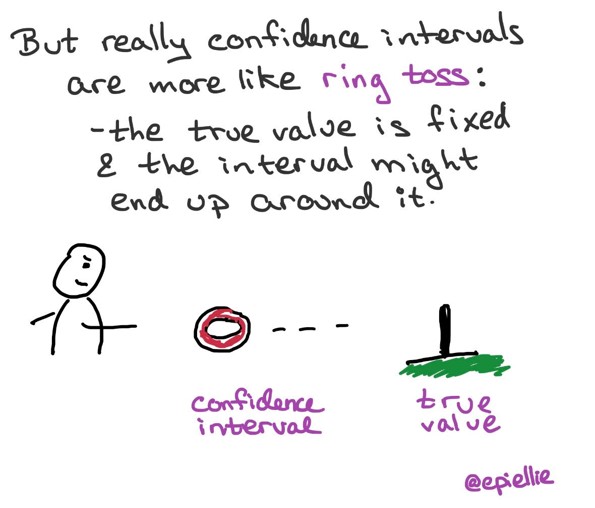

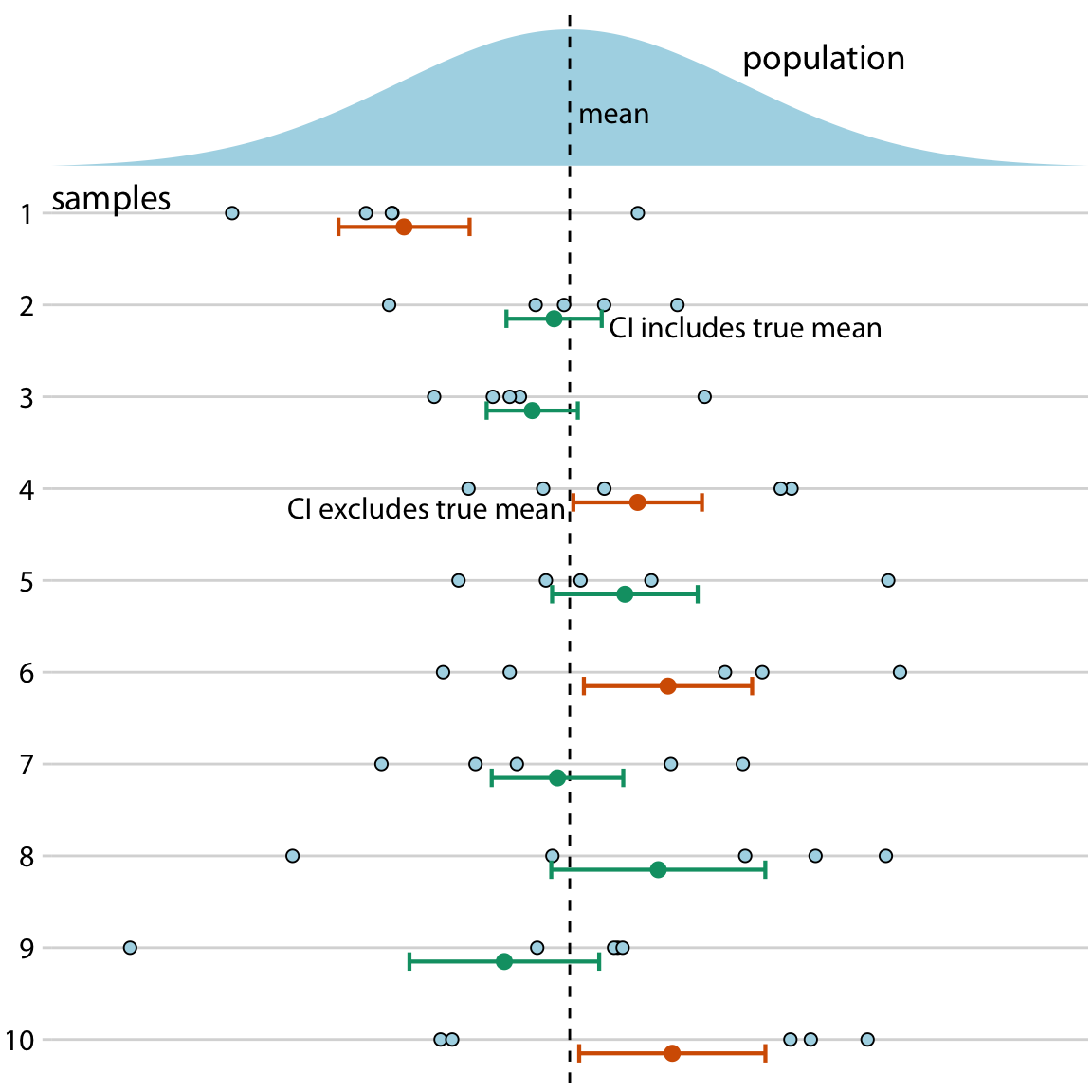

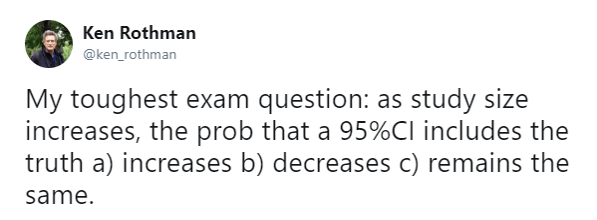

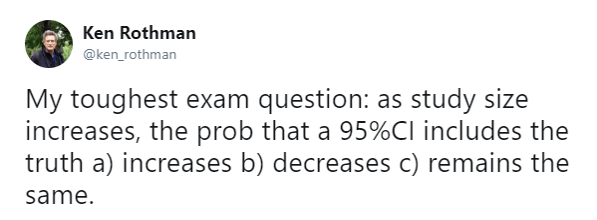

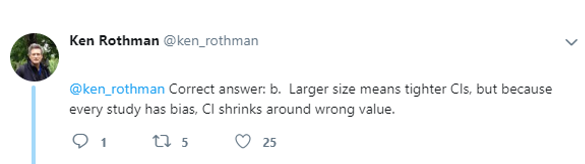

Confidence intervals

- 95% of the time 95% CI contains the true parameter

95 % refers only to how often 95 % confidence intervals computed from very many studies would contain the true size if all the assumptions used to compute the intervals were correct

- Claus Wilke, Data visualization

- Greenland S, Senn SJ, Rothman KJ, et al. Statistical tests, P values, confidence intervals, and power: a guide to misinterpretations. Eur J Epidemiol. 2016;31(4):337-350. link

Estimate and confidence level

Association measure estimate

- Risk difference

- Risk ratio

- Odds ratio

- Rate difference

- Rate ratio

- Hazard ratio

95% confidence interval (CI)

How often 95 % confidence intervals computed from many studies would contain the true effect size if all the assumptions used to compute the intervals were correct

- Uncertainty in an epidemiologic result under assumption of random error alone → often unrealistic

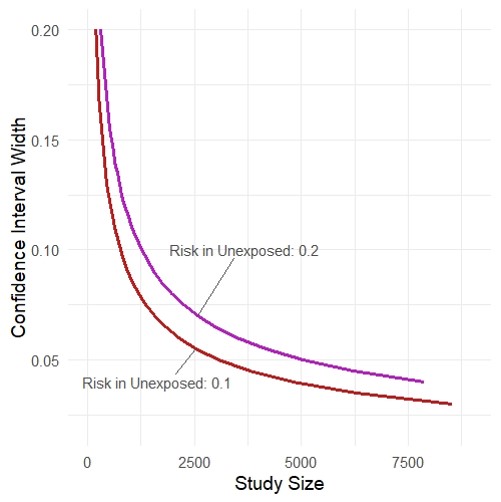

Study size and precision

- Rothman KJ, Greenland S. Planning Study Size Based on Precision Rather than Power. Epidemiology. Published online June 14, 2018. link

- https://github.com/malcolmbarrett/precisely

Type I and II errors

20th century

The requirement of randomization in experimental design was first stated by R. A. Fisher, statistician and geneticist, in 1925 in his book Statistical Methods for Research Workers. Fisher's dictum was that randomization eliminates bias and permits a valid test of significance.

Type I error rate

- a “false-positive” mistake

- is usually represented by α, and is conventionally set to 0.05

- probability of rejecting the null hypothesis when it is true

Type II error rate

- a “false-negative” mistake

- probability of failing to reject the null hypothesis when it is false

- R. A. Fisher and his advocacy of randomization link

- Rothman, K., Greenland, S., & Lash, TL. (2008). Modern Epidemiology, 3rd Edition. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Type I and II errors

Null hypothesis significance testing

Null hypothesis

- Is a hypothesis of no association between two variables in a hypothetical superpopulation

- Compared groups were sampled in a random fashion from the hypothetical superpopulation

- Is not about the observed study groups

The difference is not "statistically significant"

- One cannot reject the null hypothesis that the superpopulation groups are different

- It does not mean that the two observed groups are the same

Rothman, K., Greenland, S., & Lash, TL. (2008). Modern Epidemiology, 3rd Edition. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

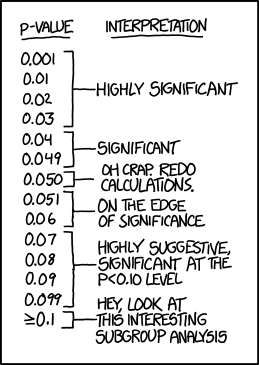

What p-value is not

- Is not the probability that the test hypothesis is true

- P value is computed assuming the test hypothesis is true

- Is not the probability that chance alone produced the observed association

- Does not say that the test hypothesis is false or should be rejected or the test hypothesis is true or should be accepted

- P>0.05 does not say that no effect was observed/absence of an effect was observed

- Null is one among the many hypotheses with P>0.05

- Does not say anything about the effect

- Very small effects or assumption violations can show statistically significant tests of the null hypothesis when the study is large

- Is not the chance of the data occurring if the test hypothesis is true

Greenland S, Senn SJ, Rothman KJ, Carlin JB, Poole C, Goodman SN, et al. Statistical tests, P values, confidence intervals, and power: a guide to misinterpretations. Eur J Epidemiol. 2016;31(4):337-50.

P-value

The probability that a test statistic computed from the data would be greater than or equal to its observed value, assuming that the test hypothesis is correct

- Indicates the degree to which the data conform to the pattern predicted by the test hypothesis and all the assumptions used for statistical modeling

Rothman, K., Greenland, S., & Lash, TL. (2008). Modern Epidemiology, 3rd Edition. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Greenland S, Senn SJ, Rothman KJ, Carlin JB, Poole C, Goodman SN, et al. Statistical tests, P values, confidence intervals, and power: a guide to misinterpretations. Eur J Epidemiol. 2016;31(4):337-50.

P-value

In any given study, the observed difference can be "statistically significant"

- When the model used to compute it is wrong

- Many sources of uncontrolled bias

P-value

In any given study, the observed difference can be "statistically significant"

- When the model used to compute it is wrong

- Many sources of uncontrolled bias

- Due to chance

- 0.05 alpha level

- false-positive statistically significant difference 5% of the time due to chance

P-value

In any given study, the observed difference can be "statistically significant"

- When the model used to compute it is wrong

- Many sources of uncontrolled bias

- Due to chance

- 0.05 alpha level

- false-positive statistically significant difference 5% of the time due to chance

- Dichotomization of study results based on p-values is harmful

- Cherry-picking of “significant” results

- Lack of studies reproducibility

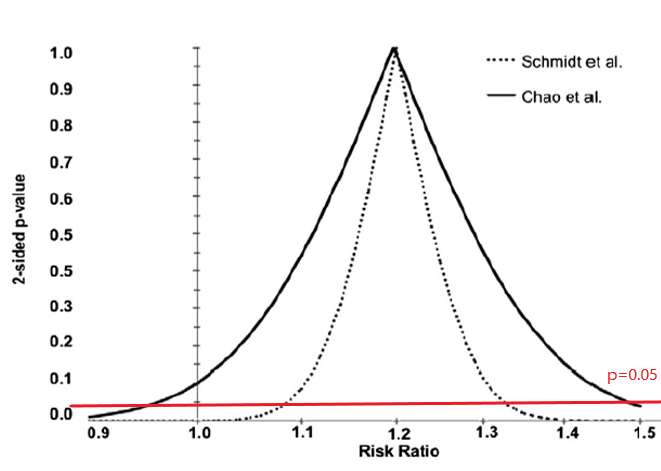

Let's discuss

- Estimation of the magnitude of the association

- 95% Confidence Interval

- Do not treat confidence interval as a substitute for a null hypothesis significance test

- Interpret 95% CI width, not whether it crosses the null value

Are these results pointing to the same conclusion or not?

- RR = 1.20 (95% CI: 0.97–1.48)

- RR = 1.20 (95% CI: 1.09–1.33)

Greenland S, Senn SJ, Rothman KJ, et al. Statistical tests, P values, confidence intervals, and power: a guide to misinterpretations. Eur J Epidemiol. 2016;31(4):337-350.

Schmidt M, Rothman KJ. Mistaken inference caused by reliance on and misinterpretation of a significance test. Int J Cardiol. 2014;177(3):1089-90.

95% Confidence Interval misinterpretation and p-value function

Schmidt M, Rothman KJ. Mistaken inference caused by reliance on and misinterpretation of a significance test. Int J Cardiol. 2014;177(3):1089-90.

What's wrong here?

- https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/jaha.116.004880

Group 1 had lower risk of AF than group 2 (hazard ratio 0.90, 95% CI 0.81–0.99) There was no difference between groups 2 and 3 (hazard ratio 0.89, 95% CI 0.78–1.0009) in incidence of AF

15 min break

Threat to validity: Bias

- Can not be remedied by large (infinite) sample size

- Can not be remedied by pooling studies

- Often is larger than random error

Threat to validity: Bias

- Can not be remedied by large (infinite) sample size

- Can not be remedied by pooling studies

- Often is larger than random error

Bias

- Selection bias (=collider stratification bias)

- Confounding

- Measurement (= information) bias

- Misclassification (if discrete variables)

- Exposure, outcome, covariables

- Differential/ non-differential

- Dependent/ independent

Selection

- Selection ≠ selection bias

- Strict inclusion/exclusion criteria or sampling from a subset of a population

- Not representative of population as a whole

- May not be a problem

- Depends on how much is known about the mechanism of effect

- “Representativeness does not, in itself, deliver valid scientific inference”

- May enhance internal validity

- Potential threat to external validity

Rothman KJ, Gallacher JE, Hatch EE. Why representativeness should be avoided. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42(4):1012-4

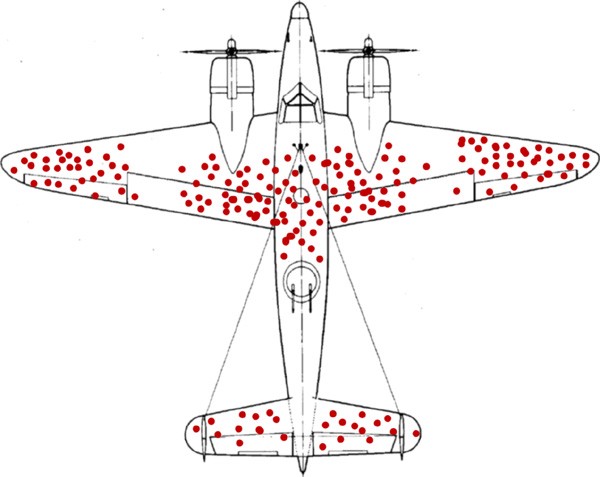

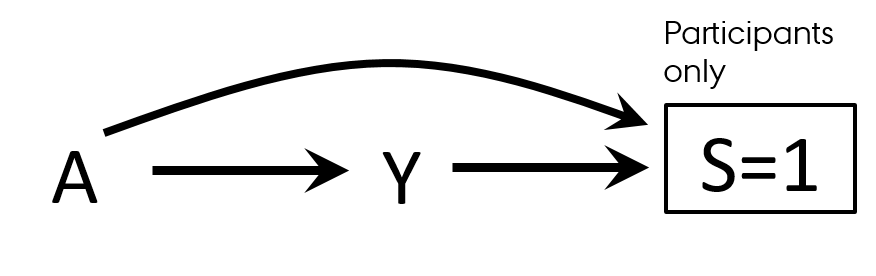

Selection bias

Errors due to systematic differences in characteristics between those who are selected for study and those who are not

survivorship bias

Selection bias

- Both exposure and outcome affect participation in the study

- At enrollment

- At follow-up

- Association is measured among participants

T.L. Lash et al. Applying Quantitative Bias Analysis to Epidemiologic Data

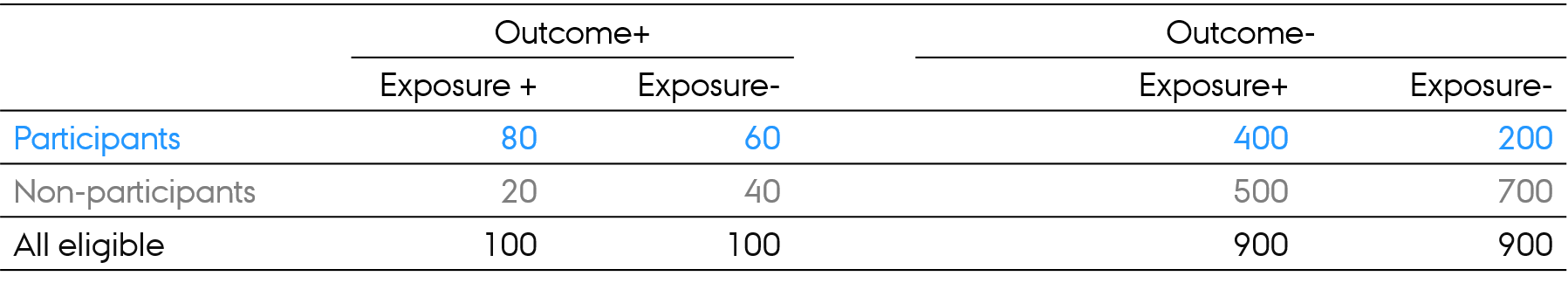

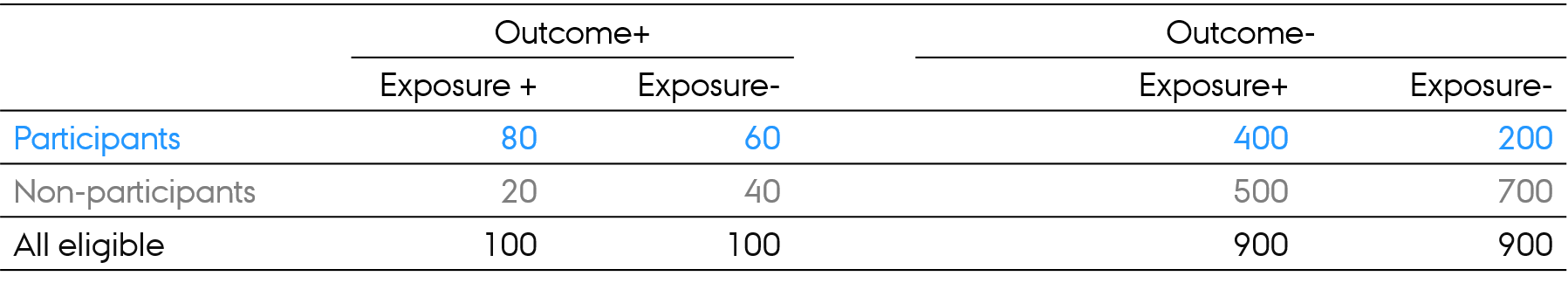

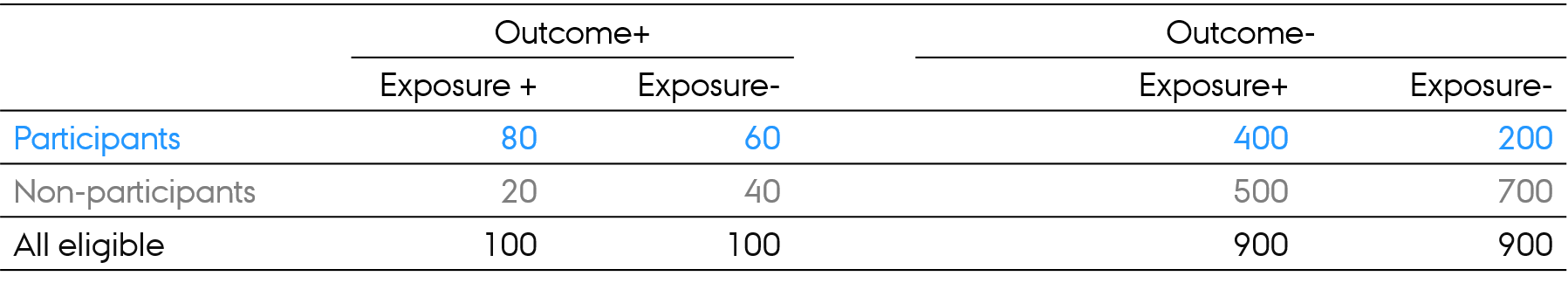

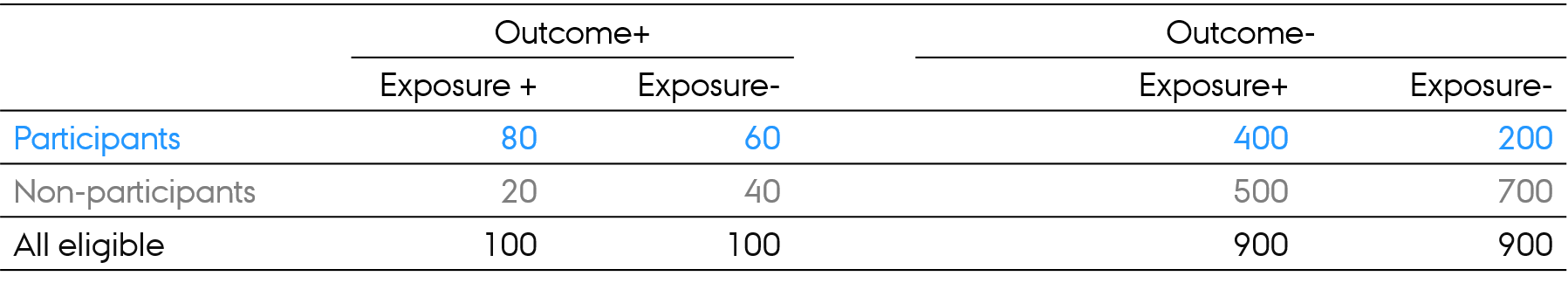

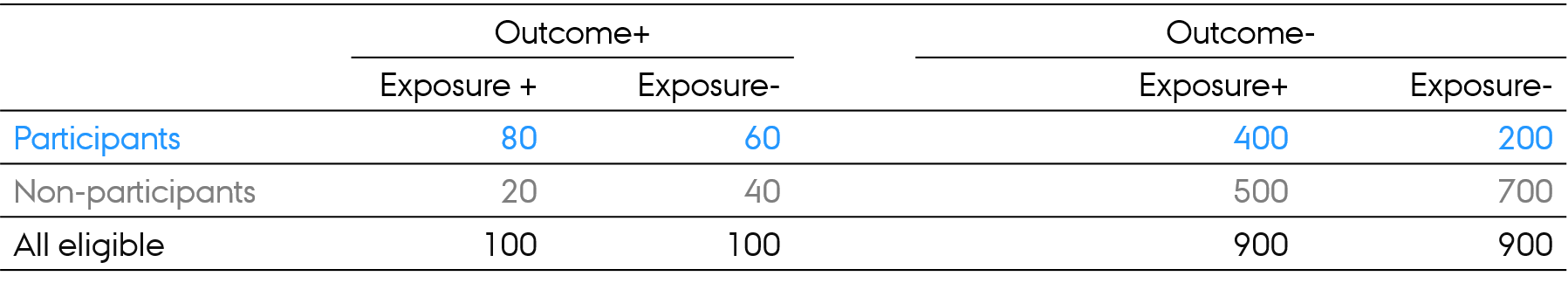

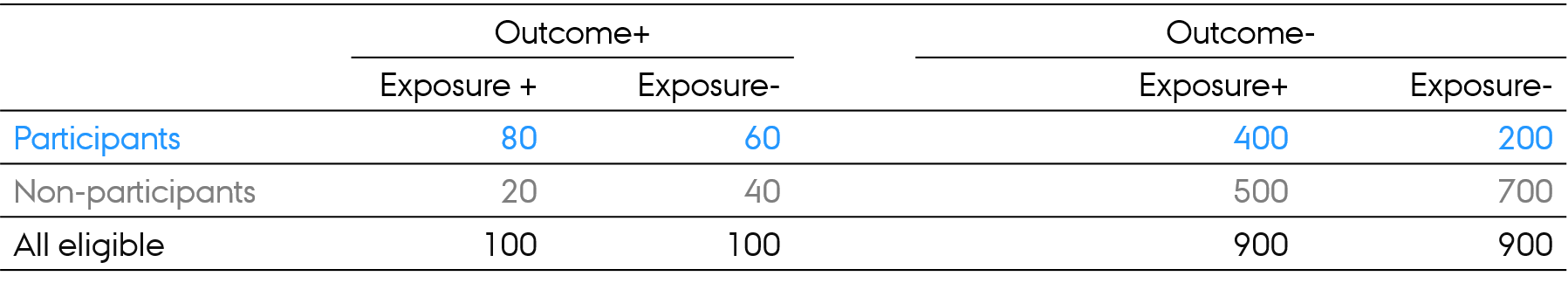

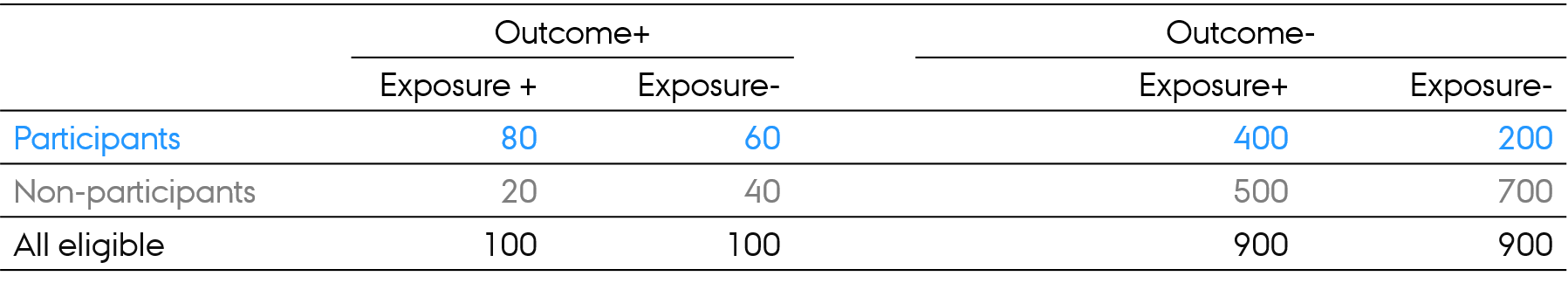

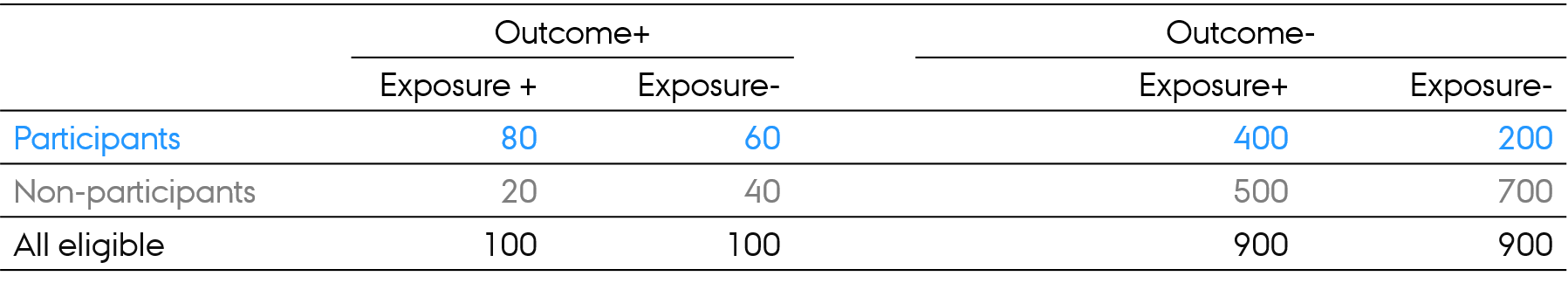

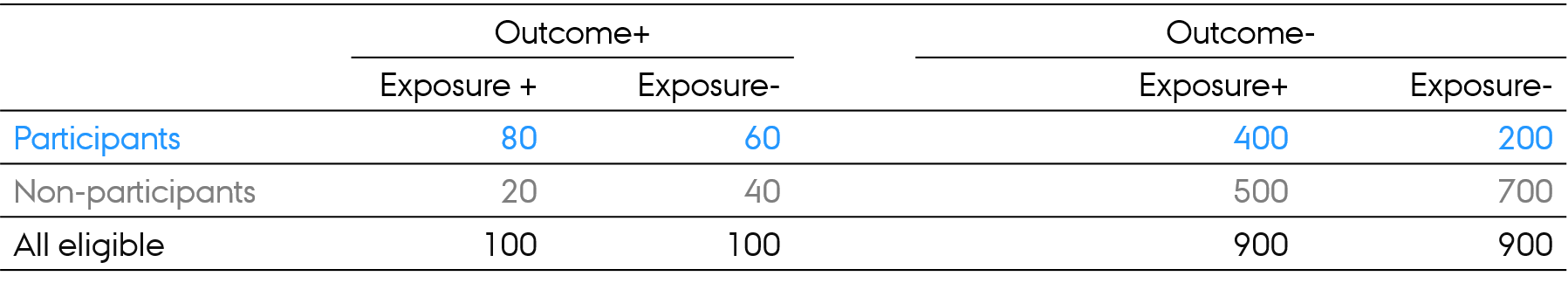

Selection bias

- Risk of the outcome in exposed and unexposed in all eligible?

Selection bias

- Risk of the outcome in exposed and unexposed in all eligible?

- 100/1000 = 10% (same outcome risk in exposed and unexposed in all eligible)

Selection bias

- Risk of the outcome in exposed and unexposed in all eligible?

- 100/1000 = 10% (same outcome risk in exposed and unexposed in all eligible)

- Exposure-Outcome association in all eligible: RR = ?

Selection bias

- Risk of the outcome in exposed and unexposed in all eligible?

- 100/1000 = 10% (same outcome risk in exposed and unexposed in all eligible)

- Exposure-Outcome association in all eligible: RR = ?

- (100/1000) / (100/1000) = 1.0

Selection bias

- Risk of the outcome in exposed and unexposed in all eligible?

- 100/1000 = 10% (same outcome risk in exposed and unexposed in all eligible)

- Exposure-Outcome association in all eligible: RR = ?

- (100/1000) / (100/1000) = 1.0

- Exposure-Outcome association in participants: RR = ?

Selection bias

- Risk of the outcome in exposed and unexposed in all eligible?

- 100/1000 = 10% (same outcome risk in exposed and unexposed in all eligible)

- Exposure-Outcome association in all eligible: RR = ?

- (100/1000) / (100/1000) = 1.0

- Exposure-Outcome association in participants: RR = ?

- (80/480) / (60/260) = 0.72

Selection bias

- Risk of the outcome in exposed and unexposed in all eligible?

- 100/1000 = 10% (same outcome risk in exposed and unexposed in all eligible)

- Exposure-Outcome association in all eligible: RR = ?

- (100/1000) / (100/1000) = 1.0

- Exposure-Outcome association in participants: RR = ?

- (80/480) / (60/260) = 0.72

- Exposure-Outcome association in nonparticipants: RR = ?

Selection bias

- Risk of the outcome in exposed and unexposed in all eligible?

- 100/1000 = 10% (same outcome risk in exposed and unexposed in all eligible)

- Exposure-Outcome association in all eligible: RR = ?

- (100/1000) / (100/1000) = 1.0

- Exposure-Outcome association in participants: RR = ?

- (80/480) / (60/260) = 0.72

- Exposure-Outcome association in nonparticipants: RR = ?

- (20/520) / (40/740) = 0.71

Selection bias

- Risk of the outcome in exposed and unexposed in all eligible?

- 100/1000 = 10% (same outcome risk in exposed and unexposed in all eligible)

- Exposure-Outcome association in all eligible: RR = ?

- (100/1000) / (100/1000) = 1.0

- Exposure-Outcome association in participants: RR = ?

- (80/480) / (60/260) = 0.72

- Exposure-Outcome association in nonparticipants: RR = ?

- (20/520) / (40/740) = 0.71

- Way of thinking: association in all eligible and in participants is different

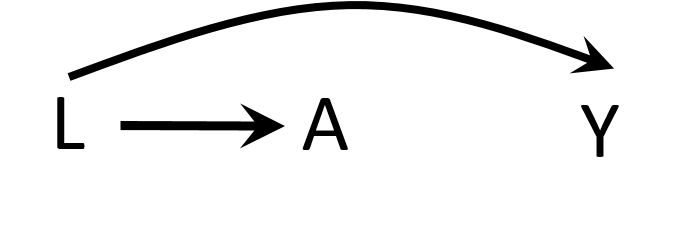

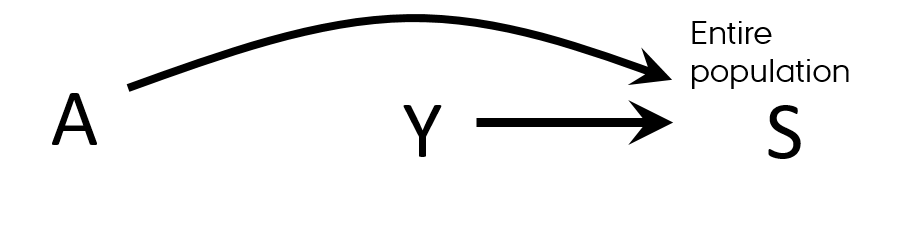

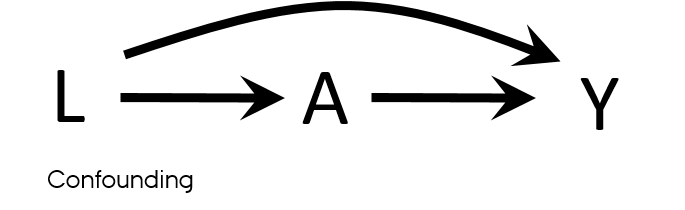

DAGs

- Directed acyclic graphs

- Very (very-very-very) quick introduction

- Drawing causal models: how world works

- Variables are associated when

- One causes another

- They have a common cause (confounding)

- They have a common consequence that has been conditioned on (selection bias)

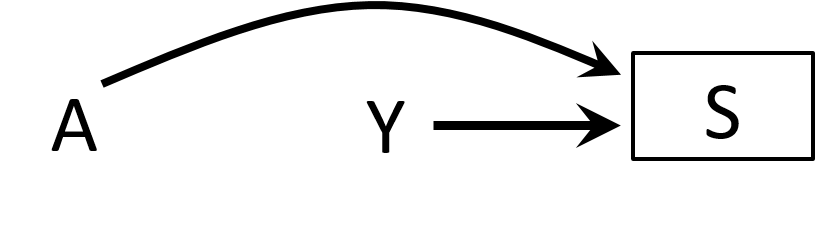

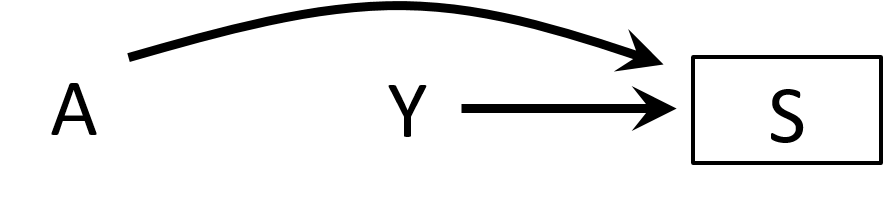

Collider stratification bias

- Structural definition of selection bias

- Collider stratification bias

- Conditioning on common effects

Hernán MA, Hernández-Díaz S, Robins JM. A Structural Approach to Selection Bias. Epidemiology. 2004;15(5):615-25.

Selection bias

- Differential participation

- Case-control study of residence proximity (A) to farms and cancer (Y)

- By definition, we start from selecting cases

- Outcome → participation (S=selection)

- People who live close to the farms are more likely to participate than those who do not live near

- Exposure → participation (S=selection)

- By conditioning on S, we open a biasing path

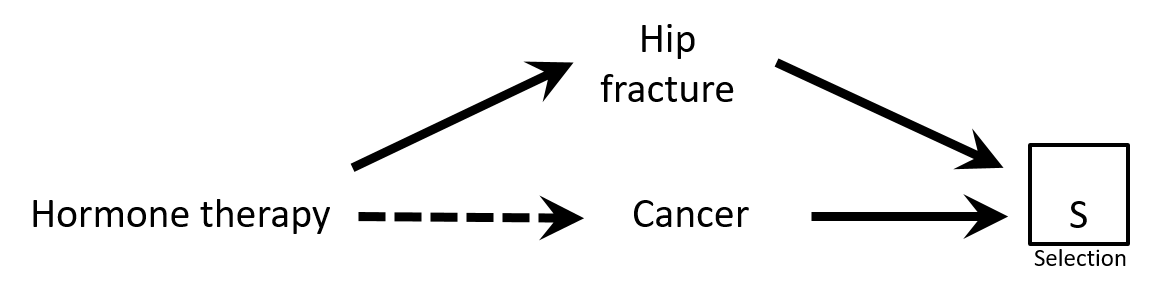

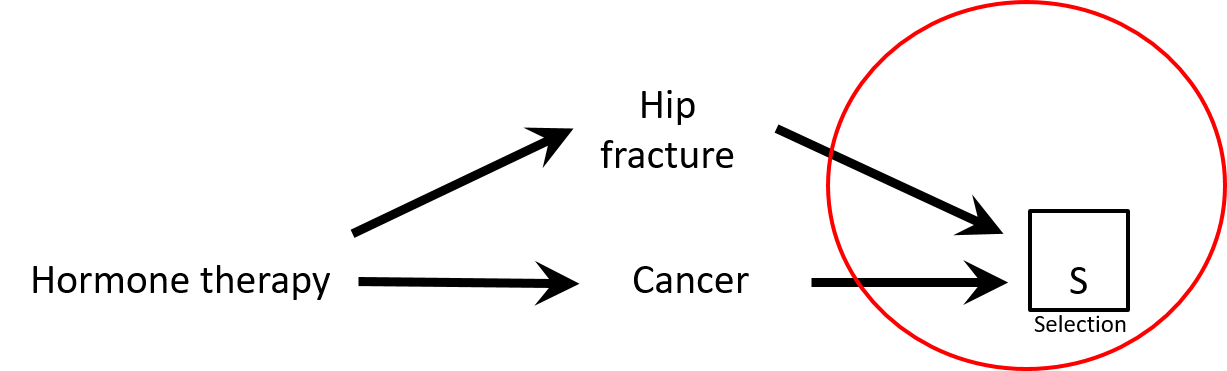

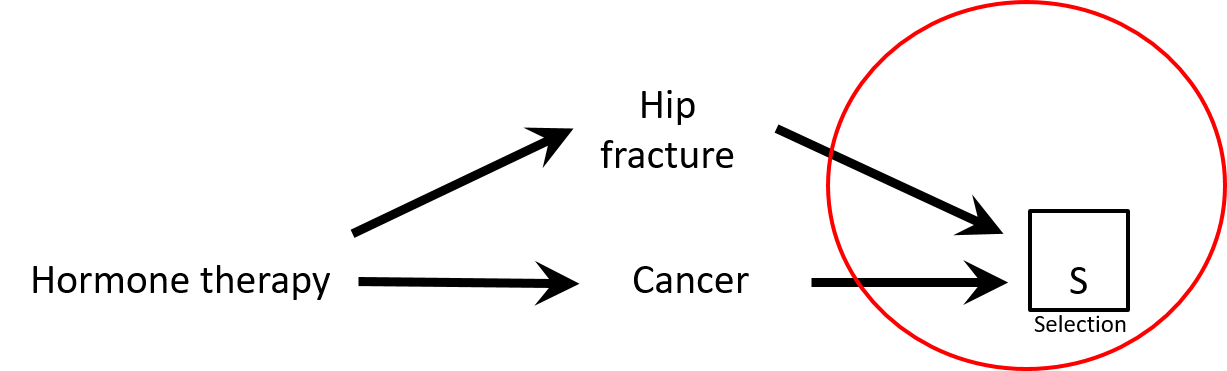

Selection bias

- Case-control study of association between hormone therapy and cancer

- Cancer cases

- Cancer controls are women hospitalized with hip fracture

- Exposure → participation?

- Would there be a selection bias in this study?

Causal Diagrams: Draw Your Assumptions Before Your Conclusions, Hernan

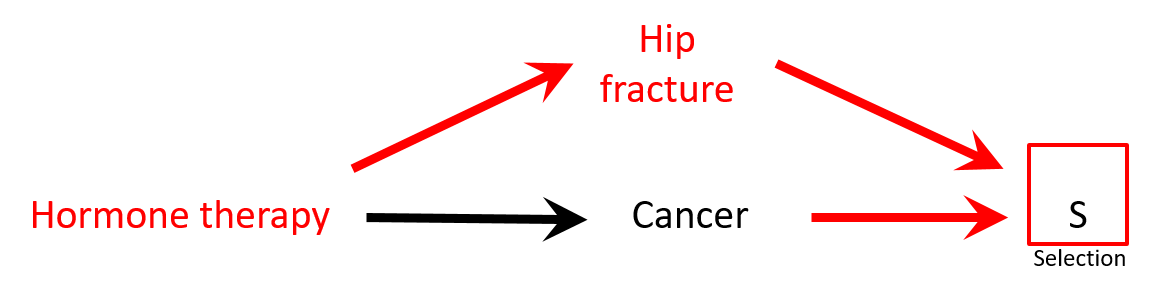

Selection bias

- There is a negative association between hormone replacement therapy (HRT) and hip fracture: HRT → ↓ risk hip fracture

- Controls are less healthy than cases: HRT seems protective against cancer while it is not (spurious association)

Selection bias

- There is a negative association between hormone replacement therapy (HRT) and hip fracture: HRT → ↓ risk hip fracture

- Controls are less healthy than cases: HRT seems protective against cancer while it is not (spurious association)

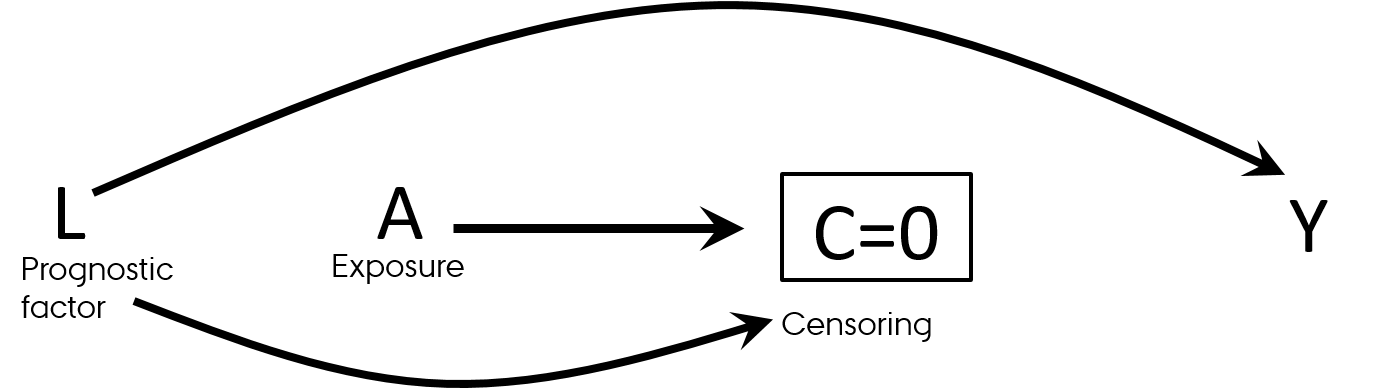

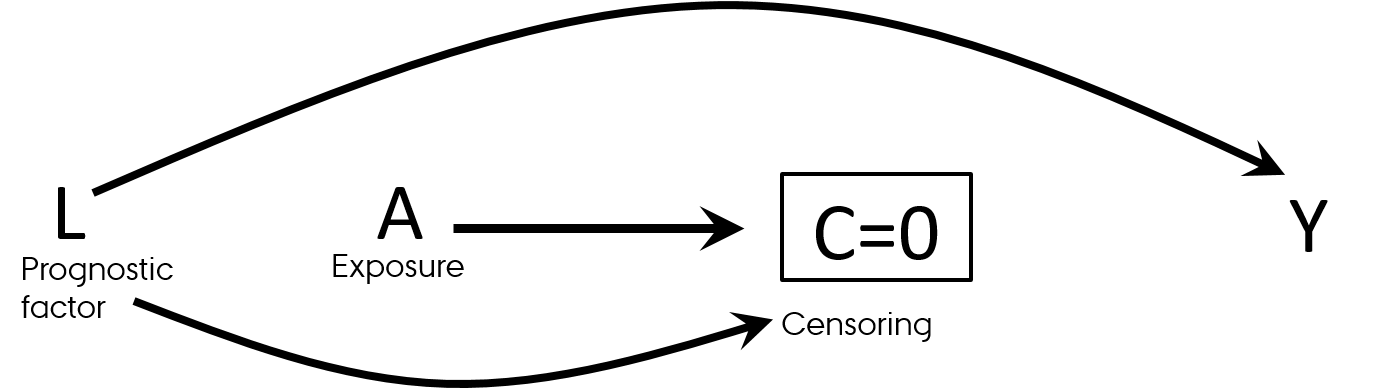

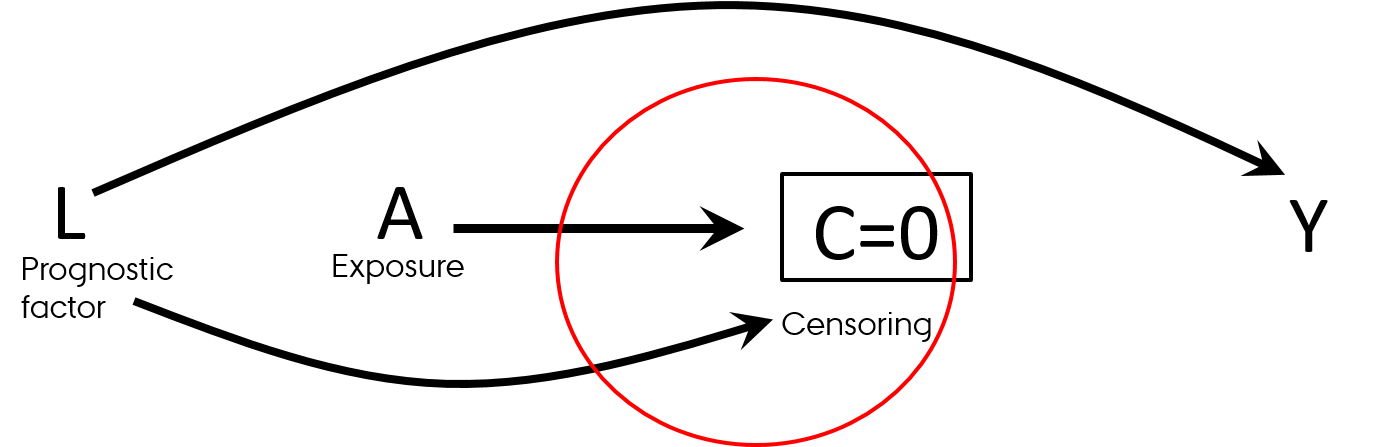

Selection bias

- Differential loss to follow-up (informative censoring)

- Follow-up studies (observational and RCTs)

- Effect in those who was not lost to follow-up

- Think "survivorship bias"

Selection bias

- Differential loss to follow-up (informative censoring)

- Follow-up studies (observational and RCTs)

- Effect in those who was not lost to follow-up

- Think "survivorship bias"

Causal Diagrams: Draw Your Assumptions Before Your Conclusions, Hernan

Selection bias

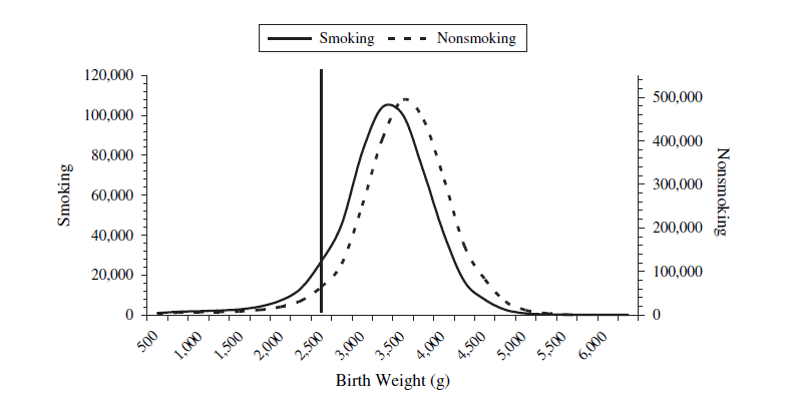

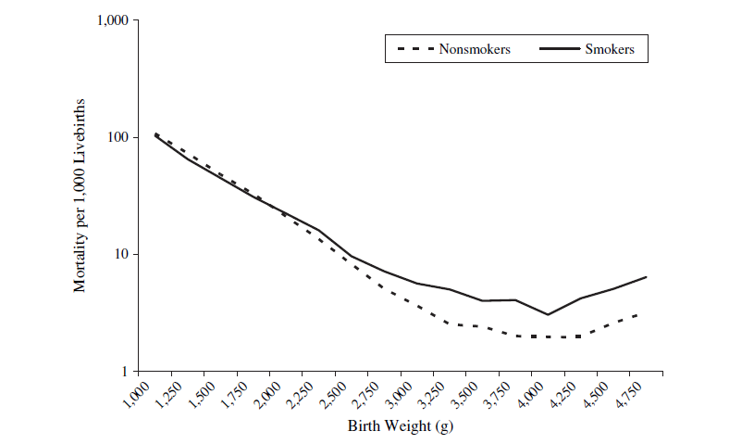

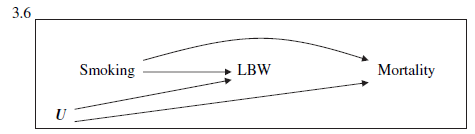

Birth weight paradox

- Infant mortality ~ Smoking: RR = 1.55

- Infant mortality ~ Smoking + Birth weight: RR = 1.05

- Was it a good decision to adjust for birth weight in this model?

The birth weight "paradox" uncovered?

Selection bias

Birth weight paradox

- Strata < 2,000 g (LBW):

- Infant mortality ~ Smoking: RR = 0.79

- Strata >= 2,000 g (not-LBW): RR=1.80

The birth weight "paradox" uncovered?

Selection bias has many names

- Inappropriate selection of controls (case-control studies)

- Competing risks

- Differential loss-to-follow-up (informative censoring)

- Berkson’s bias

- Self-selection bias/Volunteer Bias

- Healthcare access bias

- Healthy worker bias

- Healthy adherer bias

- Sick stopper bias

- Non-response bias

- Matching (case-control studies)

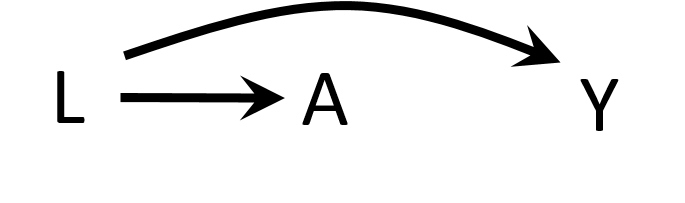

Let's discuss

- Effect of smoking on diabetes

- What to adjust for?

HarvardX PH559x Causal Diagrams: Draw Your Assumptions Before Your Conclusions

HarvardX PH559x Causal Diagrams: Draw Your Assumptions Before Your Conclusions

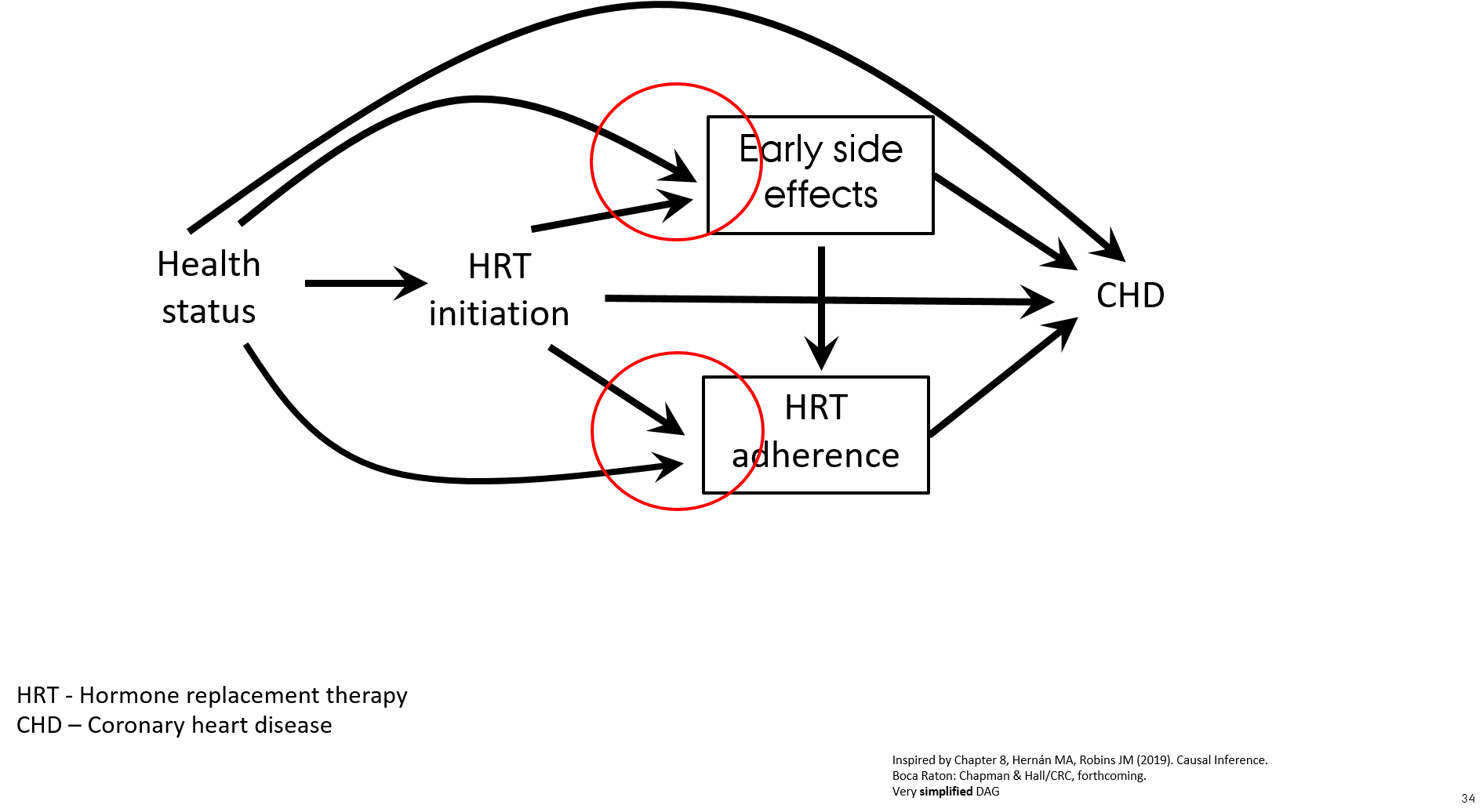

Let's discuss

- Observational cohort study of effect of hormone replacement therapy (HRT) on the risk of coronary heart disease (CHD)

- Prevalent and new users of HRT are included in the study

- Follow-up starts at enrollment for both initiators and prevalent users

- HR for CHD for current users HRT vs. never users HRT was 0.72 (Nurses’ Health Study, Grodstein, 2006)

- RCT of effect of HRT on the risk of CHD

- Intention-to-treat analysis (effect of randomization)

- Follow-up starts from the date of HRT initiation

- HR for CHD for users HRT vs. not users HRT was 1.24 (Women’s Health Initiative, Manson, 2003)

- What went wrong in the observational study?

Hernan MA, Alonso A, Logan R, Grodstein F, Michels KB, Willett WC, et al. Observational studies analyzed like randomized experiments: an application to postmenopausal hormone therapy and coronary heart disease. Epidemiology. 2008;19(6):766-79

Let's discuss

- When including prevalent and new users of HRT the association with CHD is attenuated due to the effect of prevalent users of HRT who are "long-term survivors of CHD" ("super women" who never developed CHD while on HRT)

- Healthier individuals are more likely to initiate and to stay on preventive treatment

- Treatment initiators with early side effects discontinue HRT ("depletion of susceptible women") → selection mechanism

- When asking a proper research question "what is the effect of starting HRT?" the observational cohort study shows the same results as the RCT

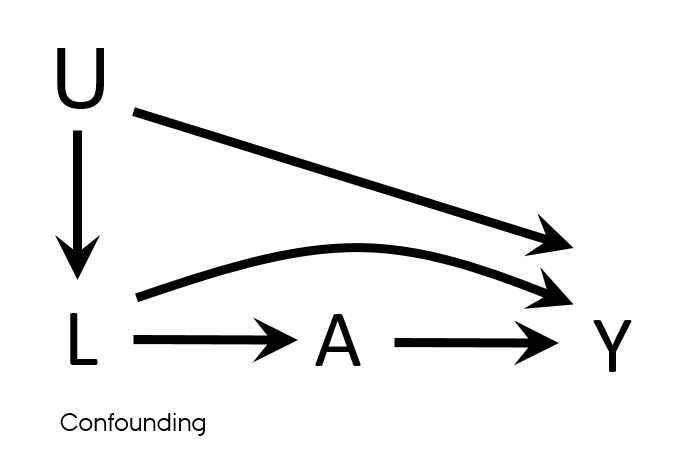

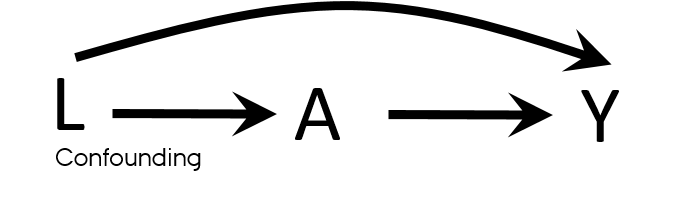

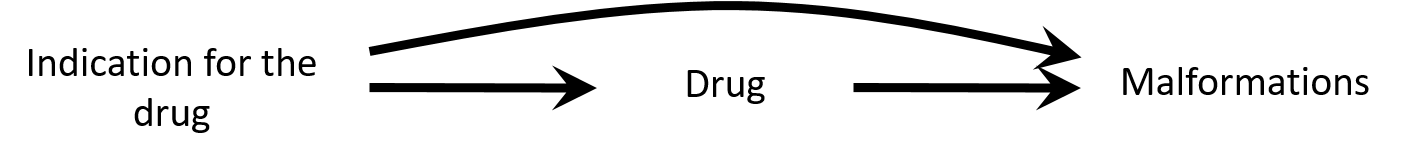

Confounding

- Mixing of the effects

- The apparent effect of the exposure of interest is distorted because the effect of an extraneous factor is mistaken for or mixed with the actual exposure effect

- Overestimation/Underestimation

- Changing direction of the effect

- Known/Unknown

- Measured/Unmeasured

- Residual

Confounding

Properties of a confounder

- Associated with the exposure

- Associated with the outcome

- Does not lie on the pathway between exposure and outcome

- Unequally distributed among the exposed and the unexposed

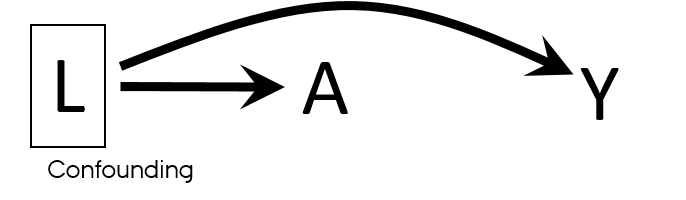

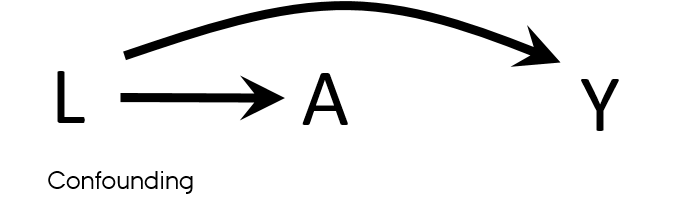

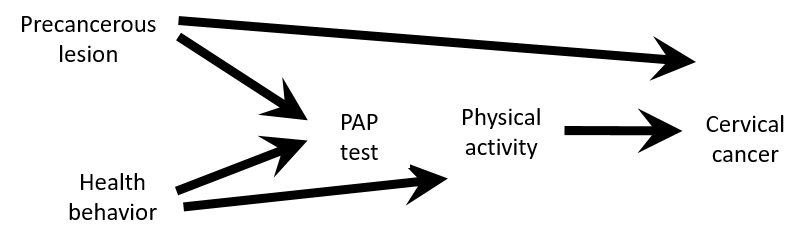

Confounding vs confounders

- Both U and L have properties used to describe confounders

- L → A

- L → Y

- U → L → A

- U → Y

- What if U is unmeasured?

- It is sufficient to adjust for L to eliminate all confounding in this DAG?

Causal Diagrams: Draw Your Assumptions Before Your Conclusions, Hernan

Confounding

Examples from your research

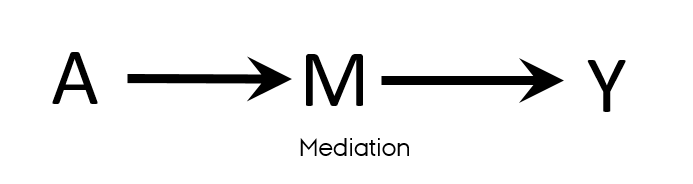

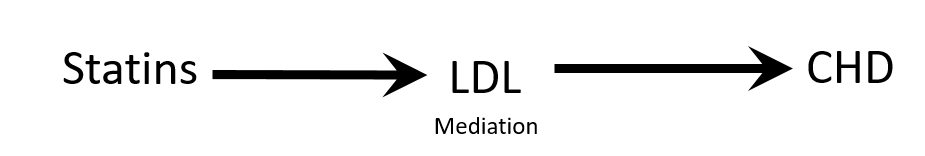

Confounding is not mediation

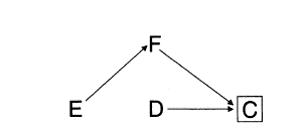

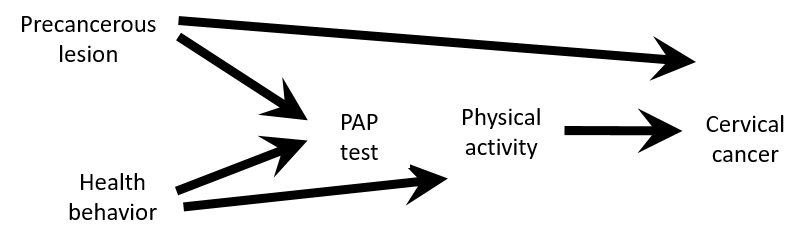

Confounding exercise

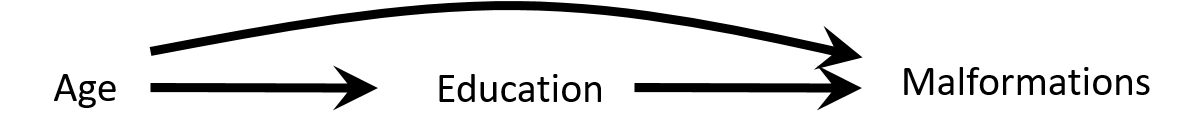

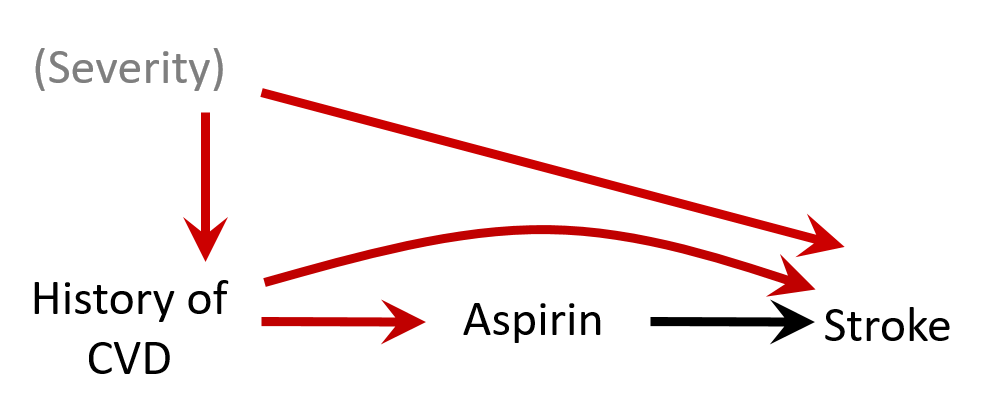

- Assume that this causal structure is true

- According to this DAG

- Is there a confounding for an association between physical activity and cervical cancer ?

- Would you stratify by or adjust for PAP-test results?

- Would you restrict the study population to women with PAP+?

Causal Diagrams: Draw Your Assumptions Before Your Conclusions, Hernan

Confounding exercise

- Despite PAP-test variable satisfy properties of a confounder

- Associated with the exposure: healthier women are more likely to take PAP test and are also more likely to be physically active PAP test ← health behaviour → physical activity

- Associated with the outcome: women with precancerous lesion will have a positive PAP test and women with precancerous lesion are at higher risk of having cervical cancer PAP test ← precancerous lesion → cervical cancer

- Not on a causal pathway

- There is no confounding

- PAP test is a collider on a path between Physical activity and Cervical cancer

- Stratifying on or adjusting for the PAP test variable would introduce bias

- Adjust for either Health behavior or Precancerous lesion if only PAP test+ population is available

“Confounding either exists or doesn't exist, but the variable may or may not be a confounder, depending on which other variables are being adjusted for.”

Causal Diagrams: Draw Your Assumptions Before Your Conclusions, Hernan

Controlling confounding

- Design

- Randomization (intervention)

- Restriction (observational)

- Matching (observational)

- Analysis

- Stratification

- Standardization

- Multivariable outcome regression

- Causal modeling (e.g., marginal structural models)

Sensitivity analyses & triangulation

- Evaluate statistical and other assumptions made when conducting the study

Challenge results

- Sensitivity analyses

- Changing definitions of exposure/outcome

- Checking possible violations of your (model) assumptions

- Bias analysis (for unmeasured or residual confounding, selection bias, etc.)

Triangulation

- Integrating results from different study designs investigating the same research question

- Each design has different sources of potential bias that are unrelated

Confounding

Take home message

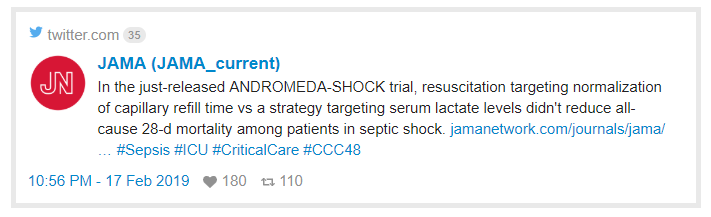

Let's discuss

Example 1

- “28-day mortality was lower with CRT (34%) than with lactate (43%) but the final Cox model shows…”

- HR:0.76 with 95% CI: 0.55-1.02

- Do you agree with the conclusion made by authors?

Let's discuss

Example 1

- “28-day mortality was lower with CRT (34%) than with lactate (43%) but the final Cox model shows…”

- HR:0.76 with 95% CI: 0.55-1.02

- Do you agree with the conclusion made by authors?

“Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence"

- The beneficial effect of CRT vs lactate is consistent with 45% reduced mortality on relative scale and 2% increased mortality on relative scale

Let's discuss

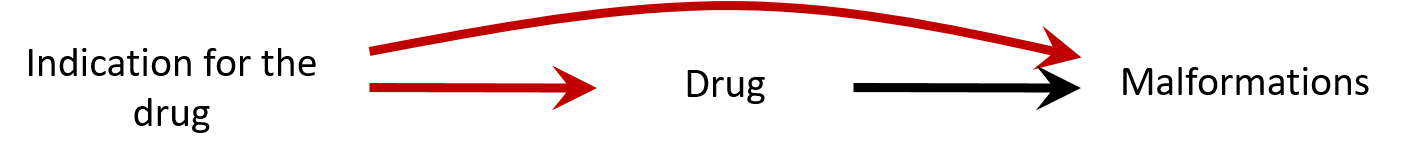

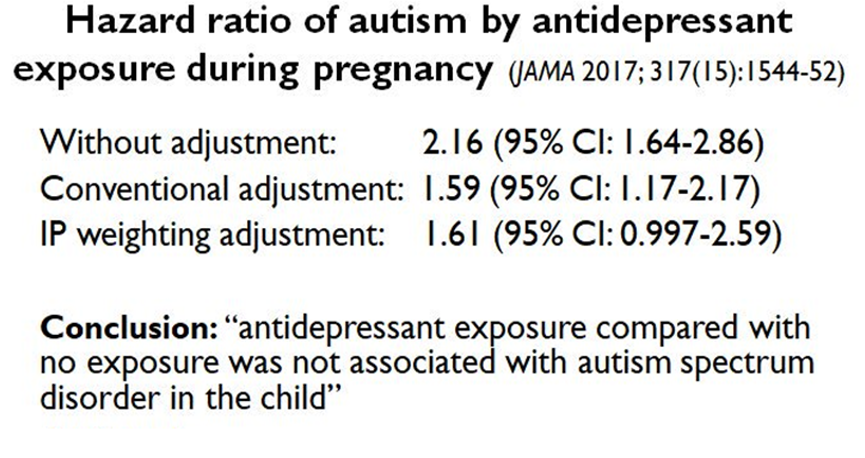

Example 2

- Do you agree or disagree with conclusion?

- Why or why not?

Let's discuss

Example 2

- Do you agree or disagree with conclusion?

- Why or why not?

- Confounding by indication: the association can be explained by insufficient control of the confounding by depression severity

- Bias (e.g. residual confounding by indication) is a threat to validity and needs to be considered when interpreting results

- E-value: https://www.evalue-calculator.com/

- The strength of an association an unmeasured confounder would need to have with exposure and the outcome beyond measured covariables to explain away the observed association

Sources for selection bias and confounding

- Confidence interval viz

- Causal Diagrams: Draw Your Assumptions Before Your Conclusions, Hernan

- The ASA's Statement on p-Values: Context, Process, and Purpose

- Statistical tests, P-values, confidence intervals, and power: a guide to misinterpretations 1.A Structural Approach to Selection Bias

- The birth weight "paradox" uncovered?

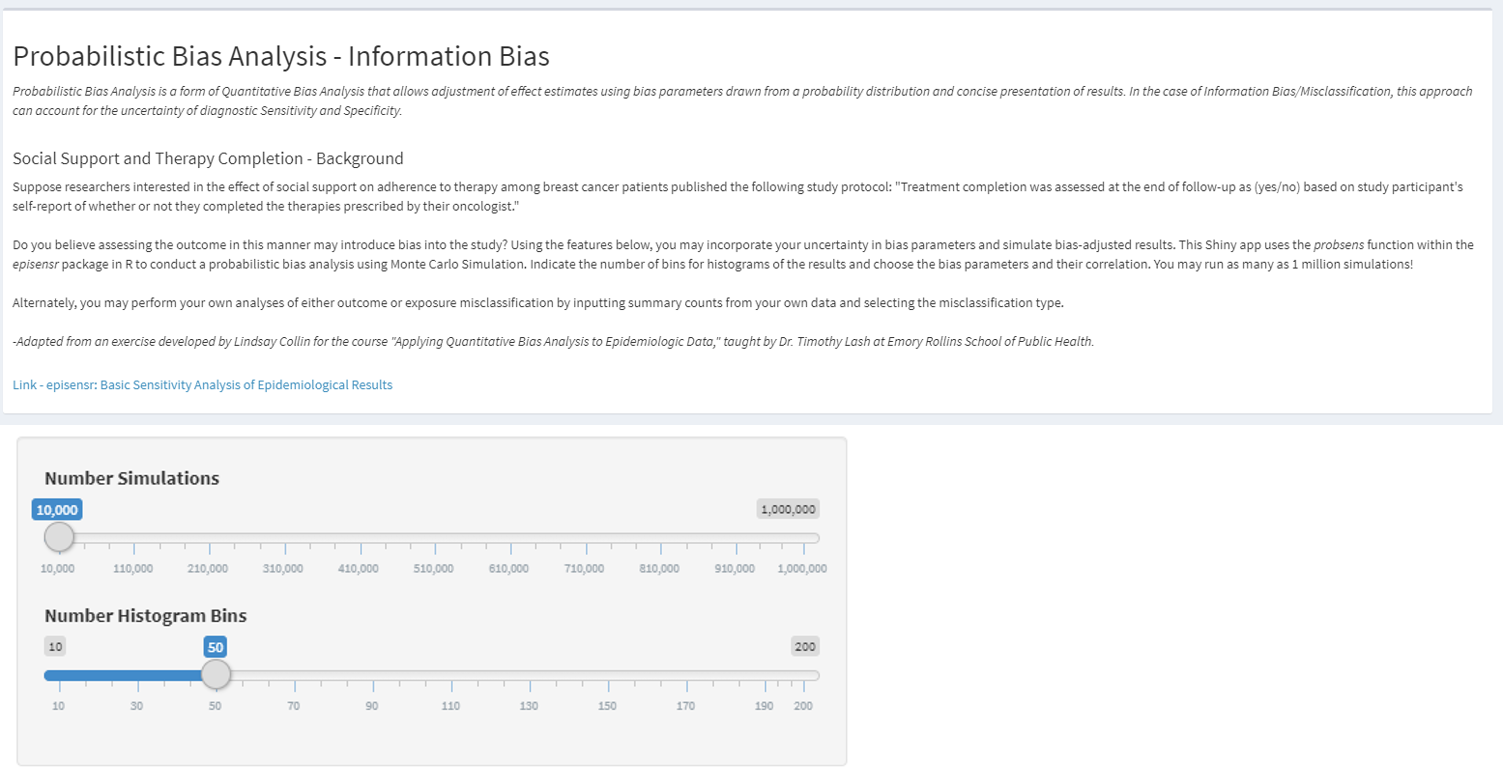

Measurement (information) bias

- Distorts the true strength of association

- Measurement bias of binary variable → misclassification

- Magnitude → Comparison with the classification obtained without error

- Differential vs non-differential

- Differential → depends on values of other variables

- Exposure assessment affected by the outcome

- Outcome assessment affected by the exposure

- Confounder assessment affected by the exposure, etc.

- Dependent vs independent

- Depends on the error in measuring other variables

- Individuals misclassified on exposure are more likely than individuals correctly classified on exposure to be misclassified on a second variable (e.g., disease status)

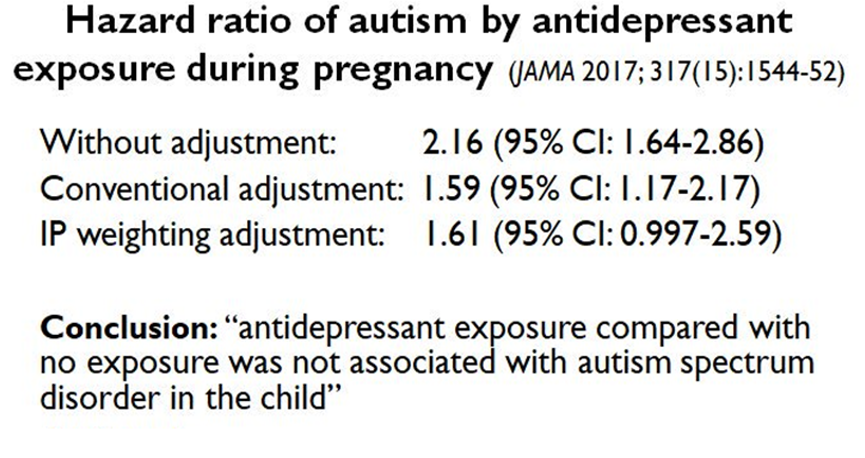

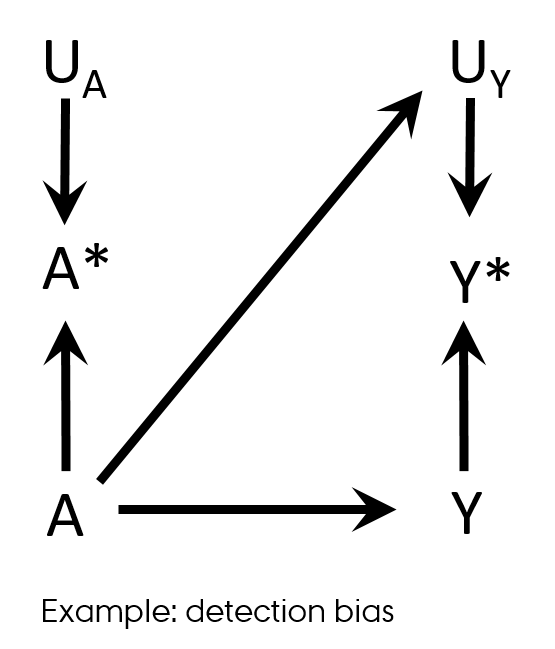

Non-differential misclassification

- Measurement errors UA and UY

- Non-differential

- Independent

- E.g. electronic medical records → entry errors

Hernán MA, Robins JM (2019). Causal Inference. Boca Raton: Chapman & Hall/CRC. Chapter 9

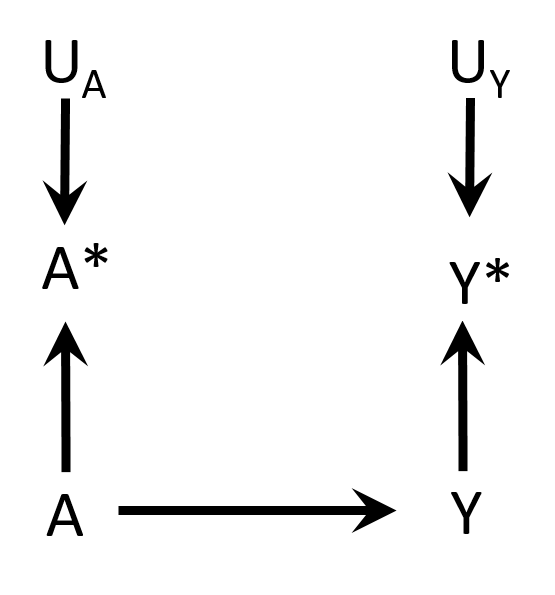

Non-differential misclassification

- Non-differential

- Dependent

Hernán MA, Robins JM (2019). Causal Inference. Boca Raton: Chapman & Hall/CRC. Chapter 9

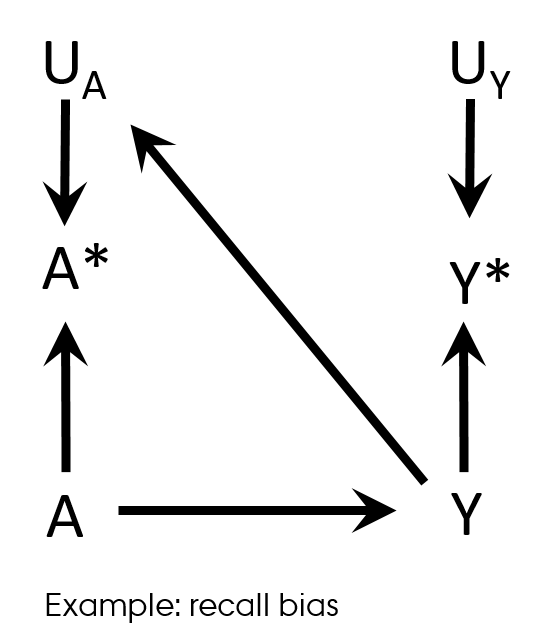

Differential misclassification

- Differential

- Independent

Hernán MA, Robins JM (2019). Causal Inference. Boca Raton: Chapman & Hall/CRC. Chapter 9

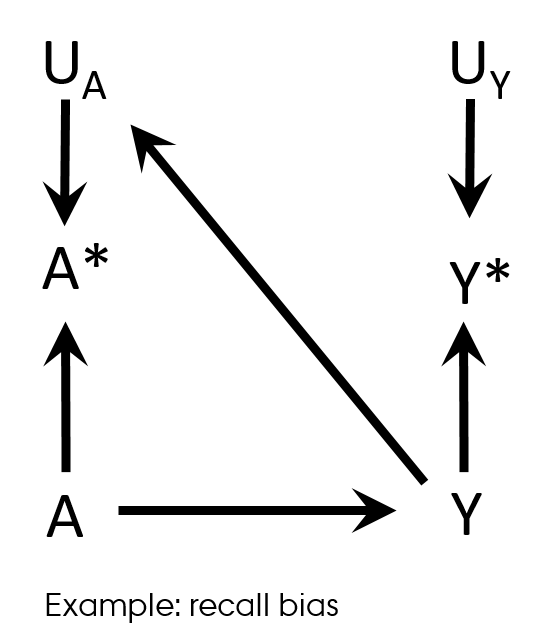

Differential misclassification

Recall bias

- Case-control study design

- Differences in accuracy or completeness of recall between controls and cases

- Differential (and non-dependent) exposure misclassification

Hernán MA, Robins JM (2019). Causal Inference. Boca Raton: Chapman & Hall/CRC. Chapter 9

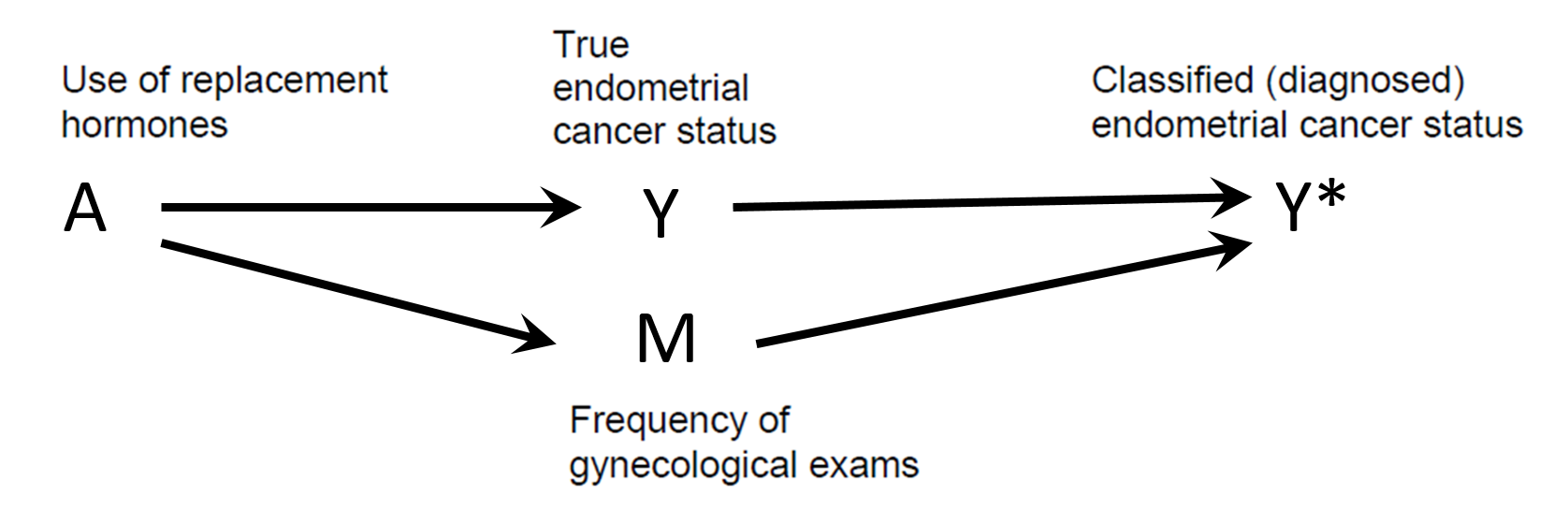

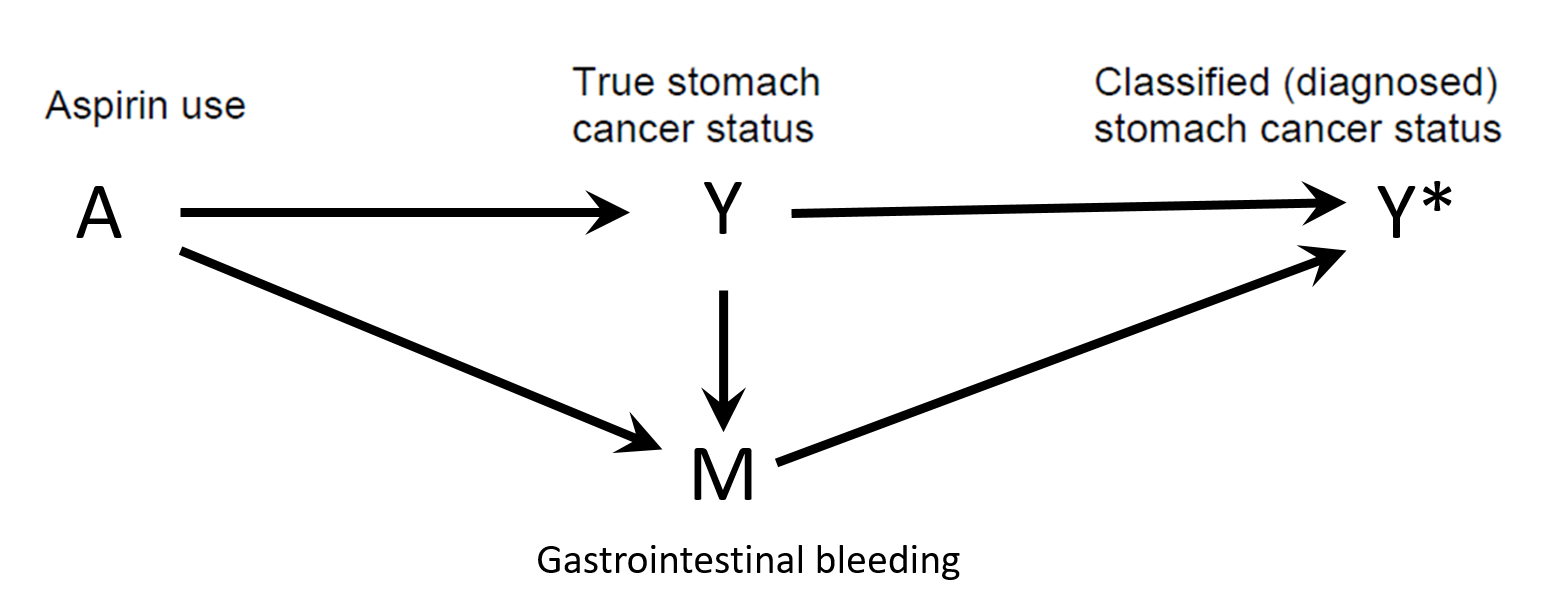

Differential misclassification

Detection bias

- Differential misclassification of the outcome in regard with exposure

Shahar E. Causal diagrams for encoding and evaluation of information bias. J Eval Clin Pract. 2009;15(3):436-40

Shahar E. Causal diagrams for encoding and evaluation of information bias. J Eval Clin Pract. 2009;15(3):436-40

Differential misclassification

Detection bias

Shahar E. Causal diagrams for encoding and evaluation of information bias. J Eval Clin Pract. 2009;15(3):436-40

Shahar E. Causal diagrams for encoding and evaluation of information bias. J Eval Clin Pract. 2009;15(3):436-40

Differential misclassification

Detection bias in RCT

- Knowledge of a patient’s assigned strategy influences outcome assessment

- Blinding

- Allocation concealment

Mansournia MA, Higgins JP, Sterne JA, Hernan MA. Biases in Randomized Trials: A Conversation Between Trialists and Epidemiologists. Epidemiology. 2017;28(1):54-9.

Exposure misclassification

- Non-differential misclassification

- True non-null exposure-outcome association & dichotomous exposure → bias towards the null (dilution of the effect)

- Can produce bias away from the null by chance for outcomes with more than 2 levels

- Differential → unpredictable

- Can simulate scenarios (simulation study)

Chubak J, Pocobelli G, Weiss NS. Tradeoffs between accuracy measures for electronic health care data algorithms. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65(3):343-9 e2.

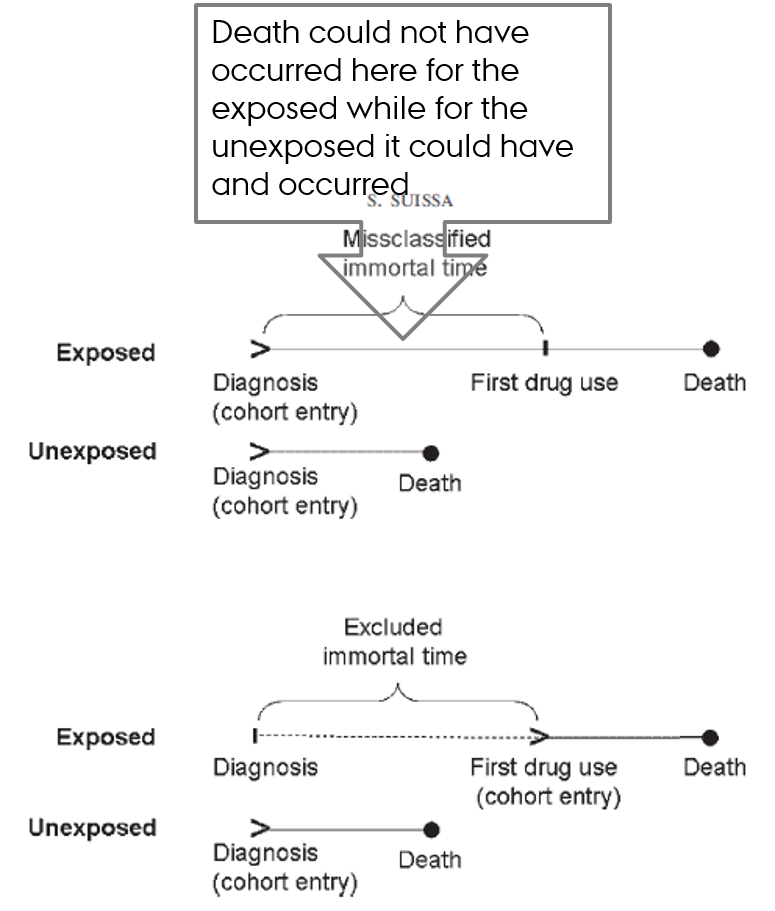

Time-related bias

- It is essentially exposure misclassification

Immortal time: intuition

- Is being awarded Oscar prolongs life?

- Immortal time bias: an actor or director had to stay alive long enough to be classified as “Oscar winner”

Immortal time bias

- Time-dependent exposure definition

- Period between cohort entry and the first prescription for the drug under study → by definition event-free in exposed

- Immortal time

- Misclassified person-time

- Ignored person-time

Suissa S. Immortal time bias in observational studies of drug effects. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2007;16(3):241-9.

Hernan MA, Sauer BC, Hernandez-Diaz S, Platt R, Shrier I. Specifying a target trial prevents immortal time bias and other self-inflicted injuries in observational analyses. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;79:70-5.

Immortal time

- Time during which the outcome could not have occurred

- Usually occurs before the person initiates treatment

- Patient must remain event-free in order to be classified as treated

- Incorrect consideration of this (untreated) time → immortal time bias

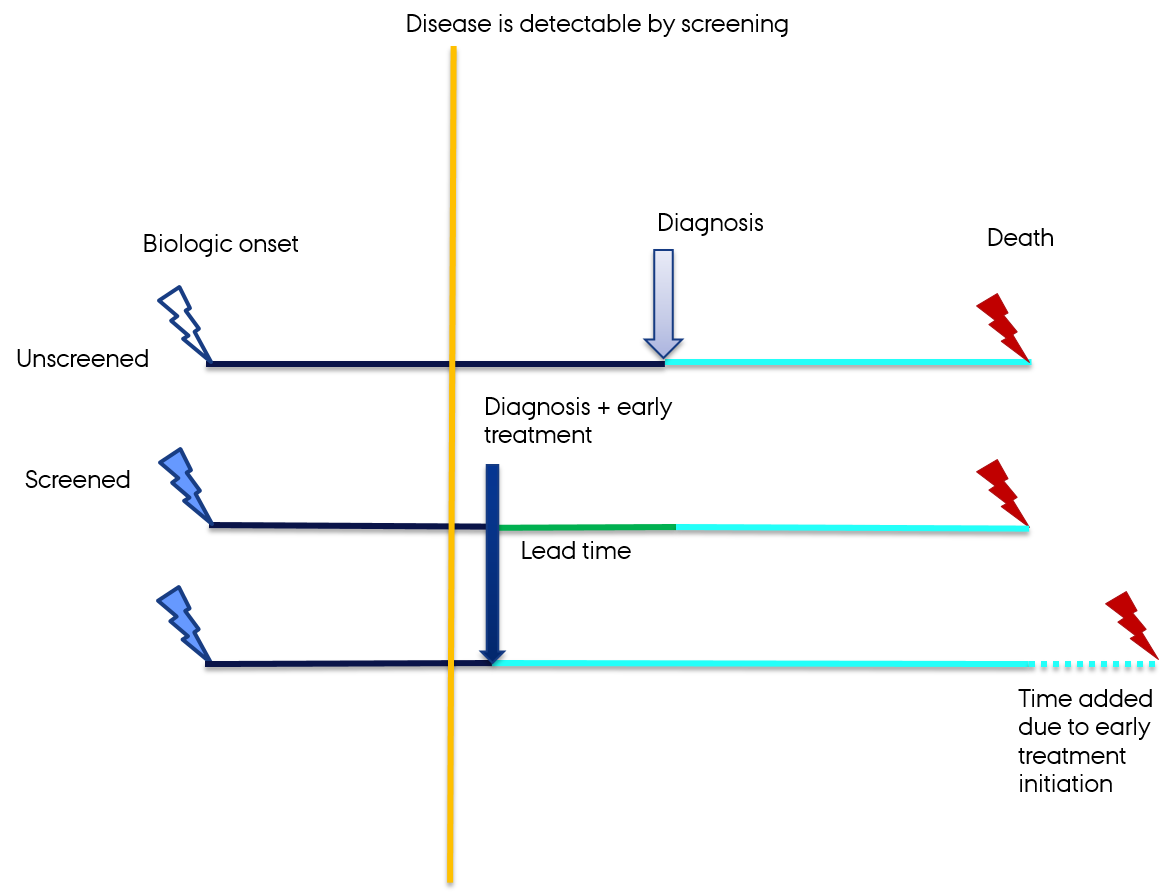

Lead time bias

- The added time of illness if the diagnosis is caught during its latency period

Delgado-Rodriguez M, Llorca J. Bias. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2004;58(8):635-41.

Delgado-Rodriguez M, Llorca J. Bias. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2004;58(8):635-41.

Outcome misclassification

- Non-differential misclassification → bias towards the null

- If high specificity → relatively unbiased

“If the disease can be defined such that there are no false-positives (i.e., specificity is 100%) and the misclassification of true positives (i.e., sensitivity) is nondifferential with respect to exposure, then risk ratio measures of effect will not be biased”

- Differential misclassification → unpredictable

- Can do simulation study

Lash TL, Fox MP, Fink AK. Applying Quantitative Bias Analysis to Epidemiologic Data. Springer. 2009

Confounder misclassification

- Non-differential misclassification of confounder

- Jeopardize confounding control → residual confounding

- Bias in the direction of confounding

- Differential misclassification of confounder

- Unpredictable

Validation studies

- Magnitude of misclassification

- Study validity

- Feed-back to clinicians

- Frequently cited papers

- Lots of work

Validation studies

- Gold standard: medical records

- Algorithm

- E.g. combination of diagnostic ICD-10 codes E10-E11 and medication ATC codes A10 → patients with diabetes

- Proportion = probability (bound to be between 0 and 1)

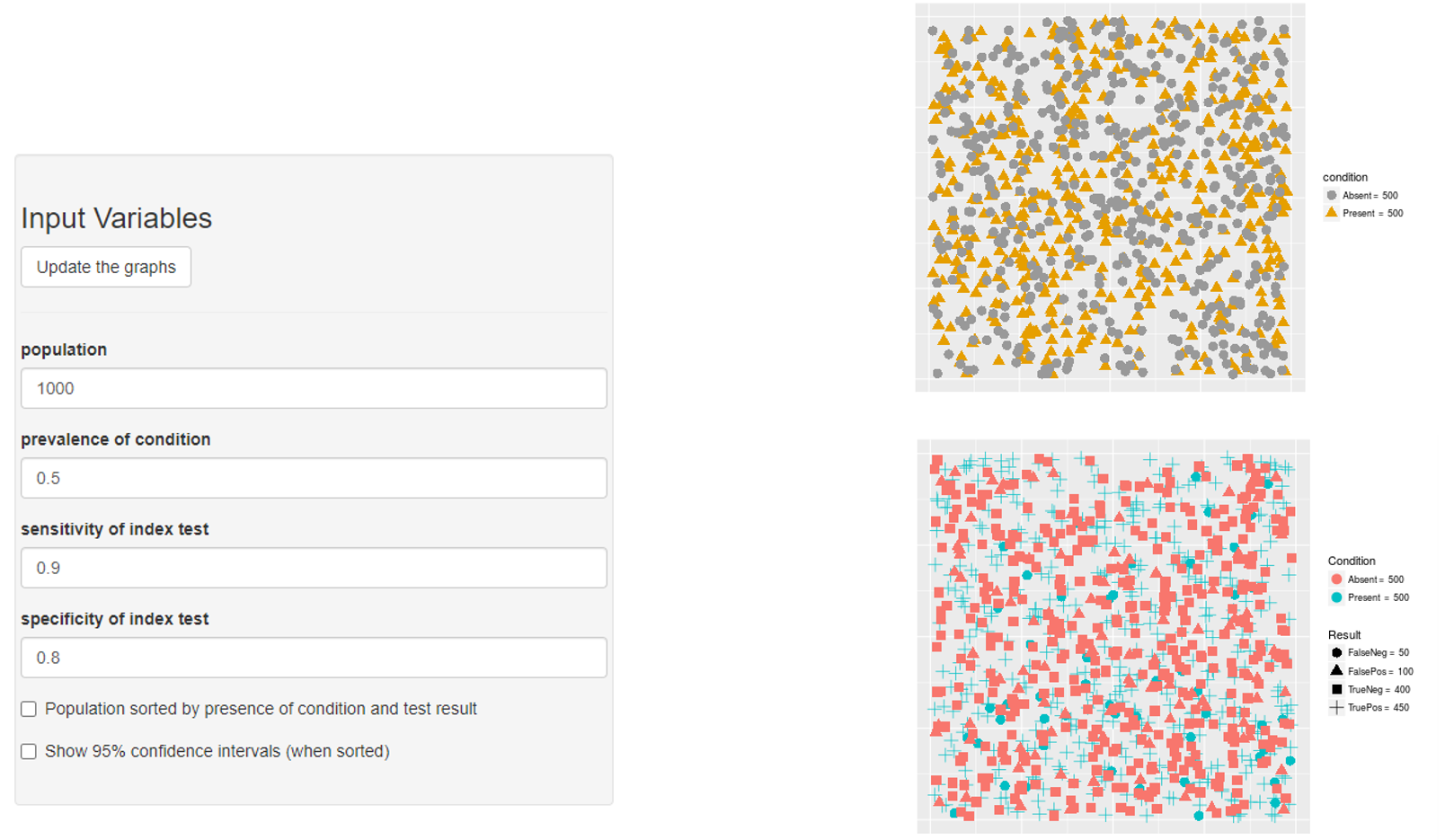

Sensitivity

- The proportion of patients with the disease of interest who are algorithm-positive

- The probability that a subject who was truly exposed was correctly classified as exposed is the classification scheme’s sensitivity (SE)

Specificity

- The proportion of persons without the disease who are algorithm-negative

- The probability that a subject who was truly unexposed was correctly classified as unexposed is the classification scheme’s specificity (SP)

FN & FP

- The proportion truly +ve who were incorrectly classified as -ve is the false-negative proportion (FN)

- The proportion incorrectly classified as -ve is the false-positive proportion (FP)

- Ehrenstein V, Petersen I, Smeeth L, et al. Helping everyone do better: a call for validation studies of routinely recorded health data. Clin Epidemiol. 2016;8:49-51

- Lash TL, Fox MP, Fink AK. Applying Quantitative Bias Analysis to Epidemiologic Data. Springer. 2009

Validation studies

PPV

- Positive predictive value

- The proportion of algorithm-positive patients who truly have the disease of interest

- The probability of truly being exposed if classified as exposed

NPV

- Negative predictive value

- The proportion of algorithm-negative persons without the disease of interest

- The probability of truly being unexposed if classified as unexposed

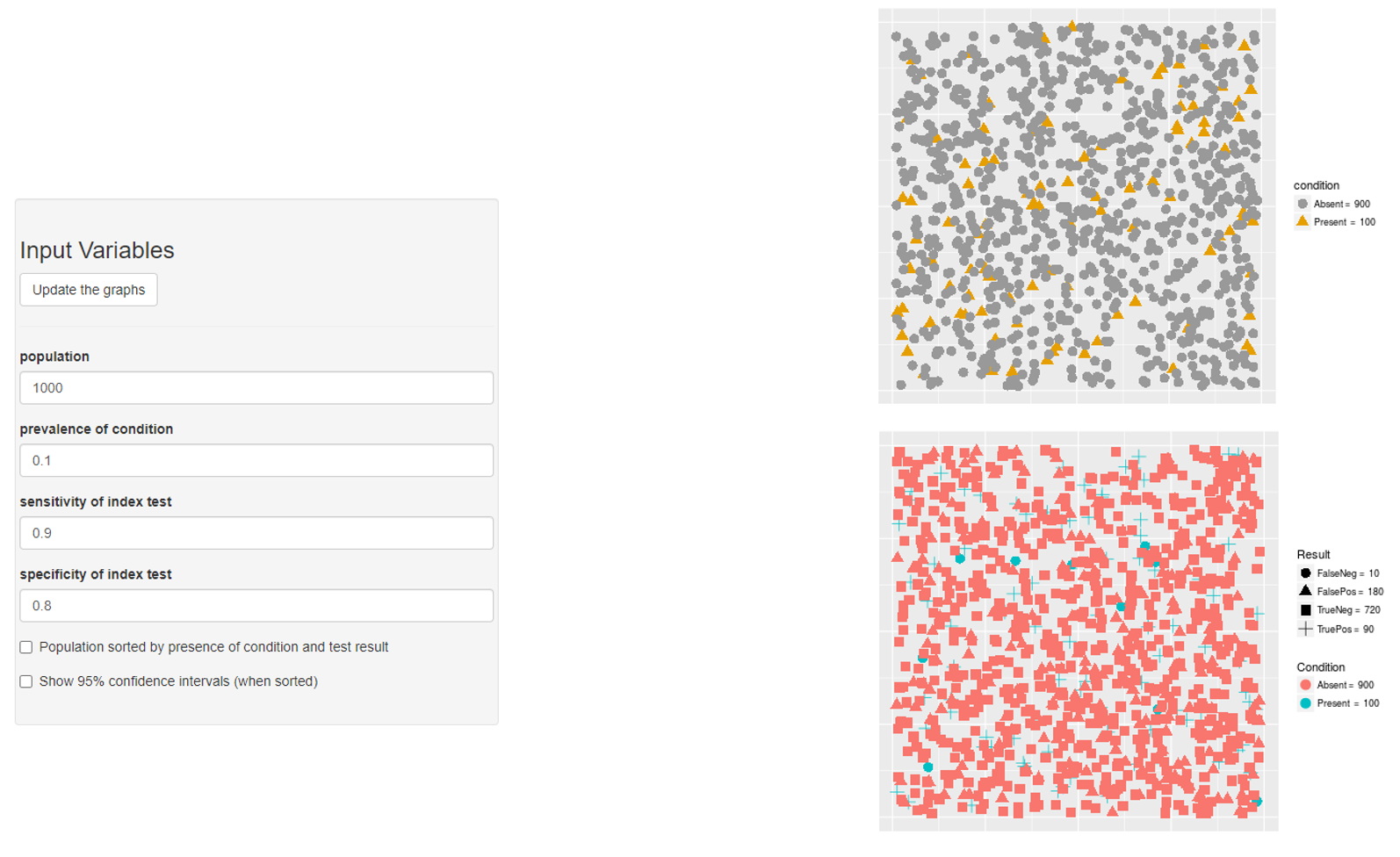

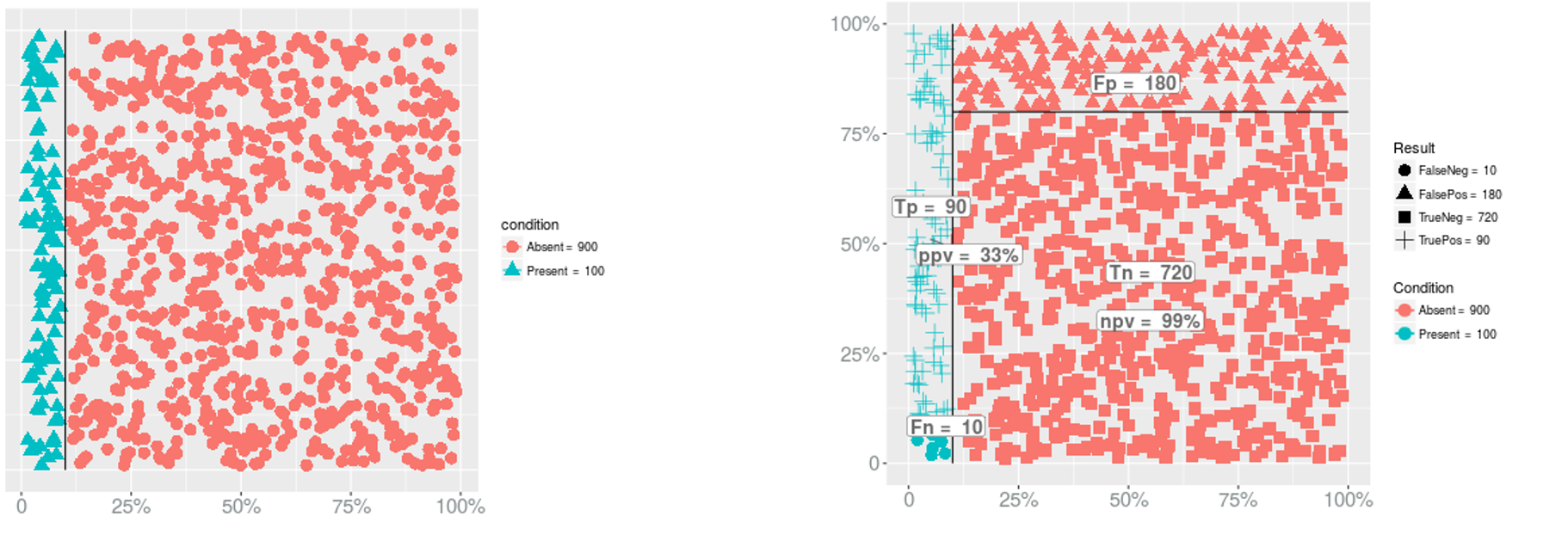

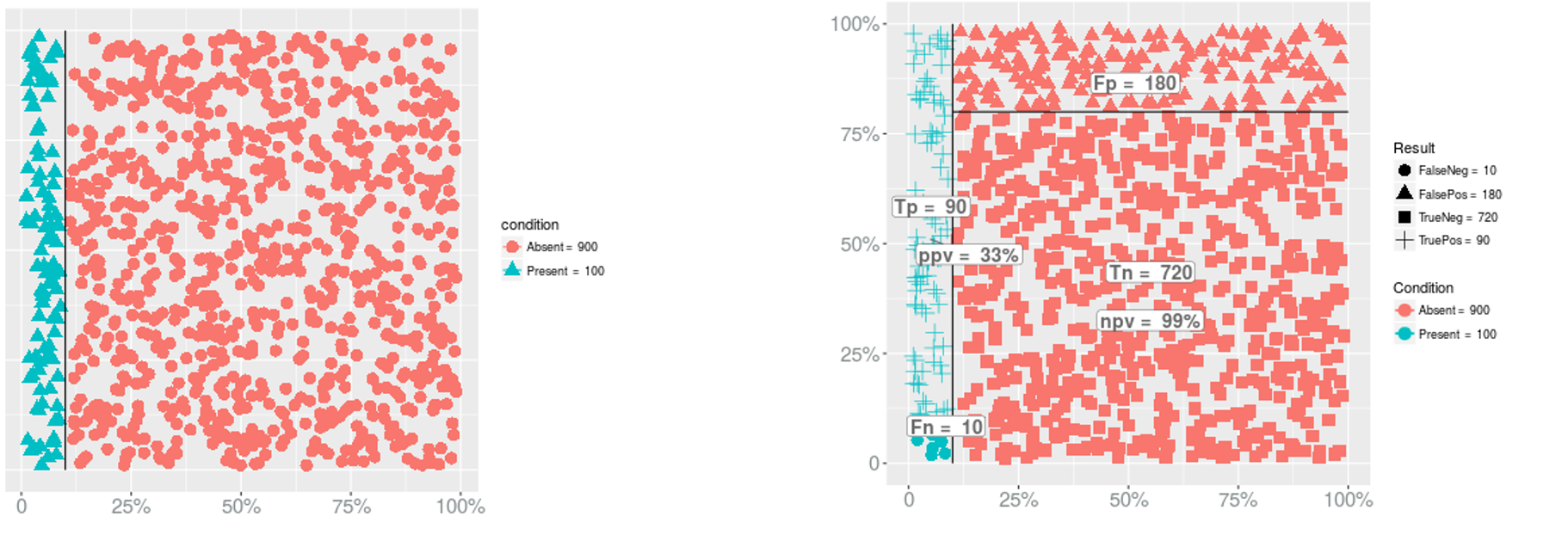

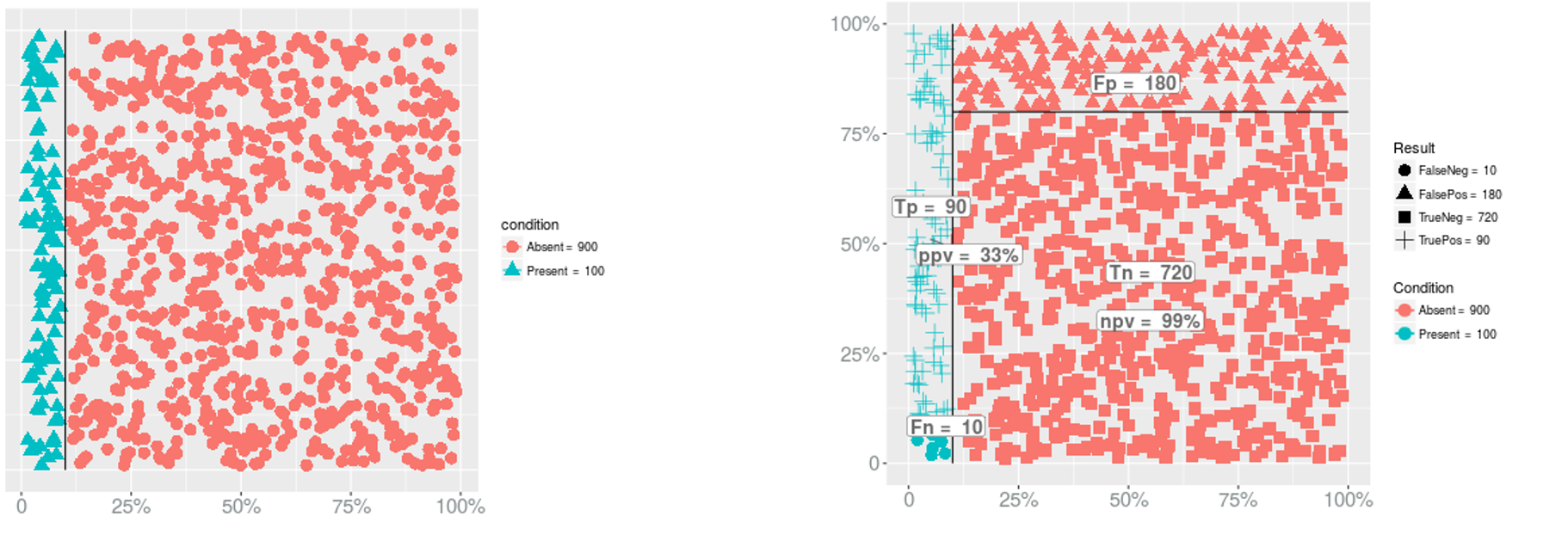

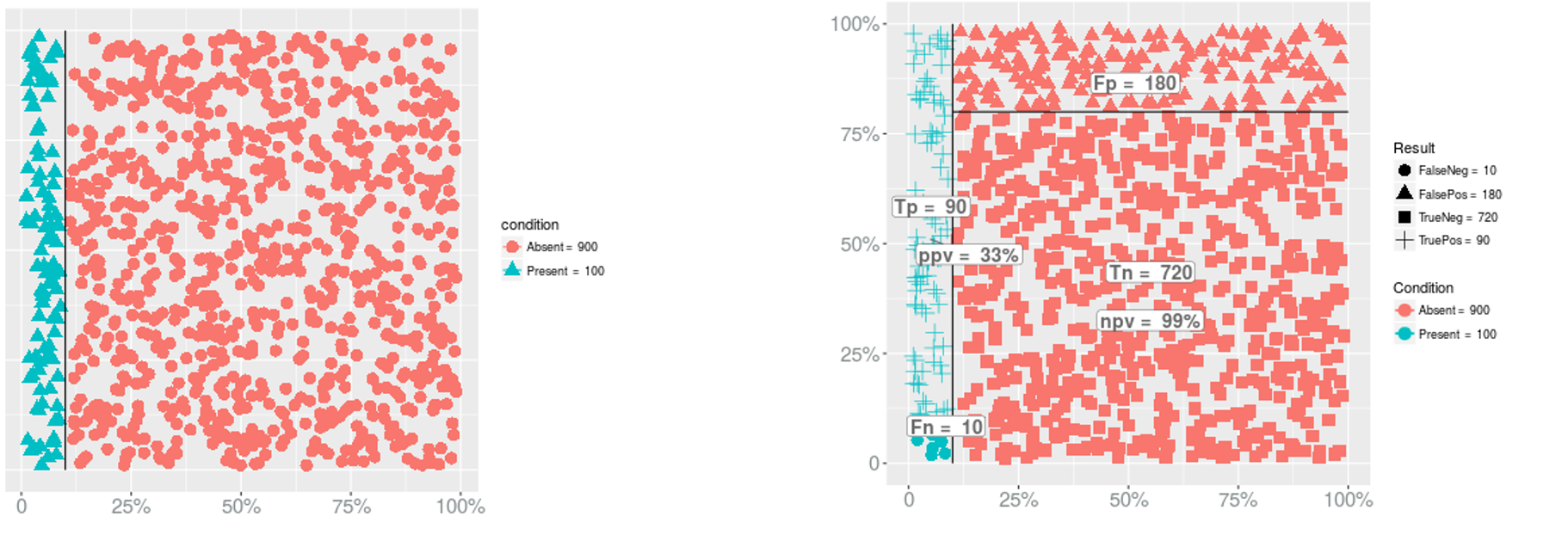

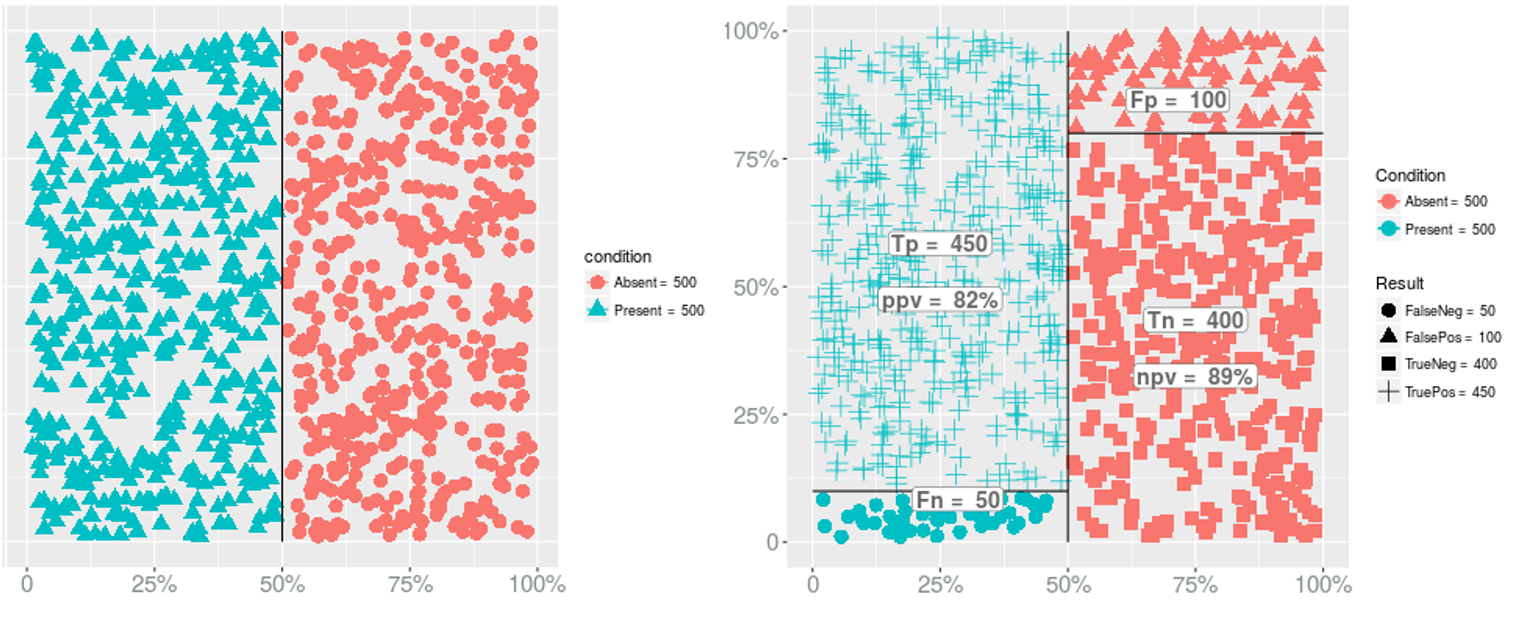

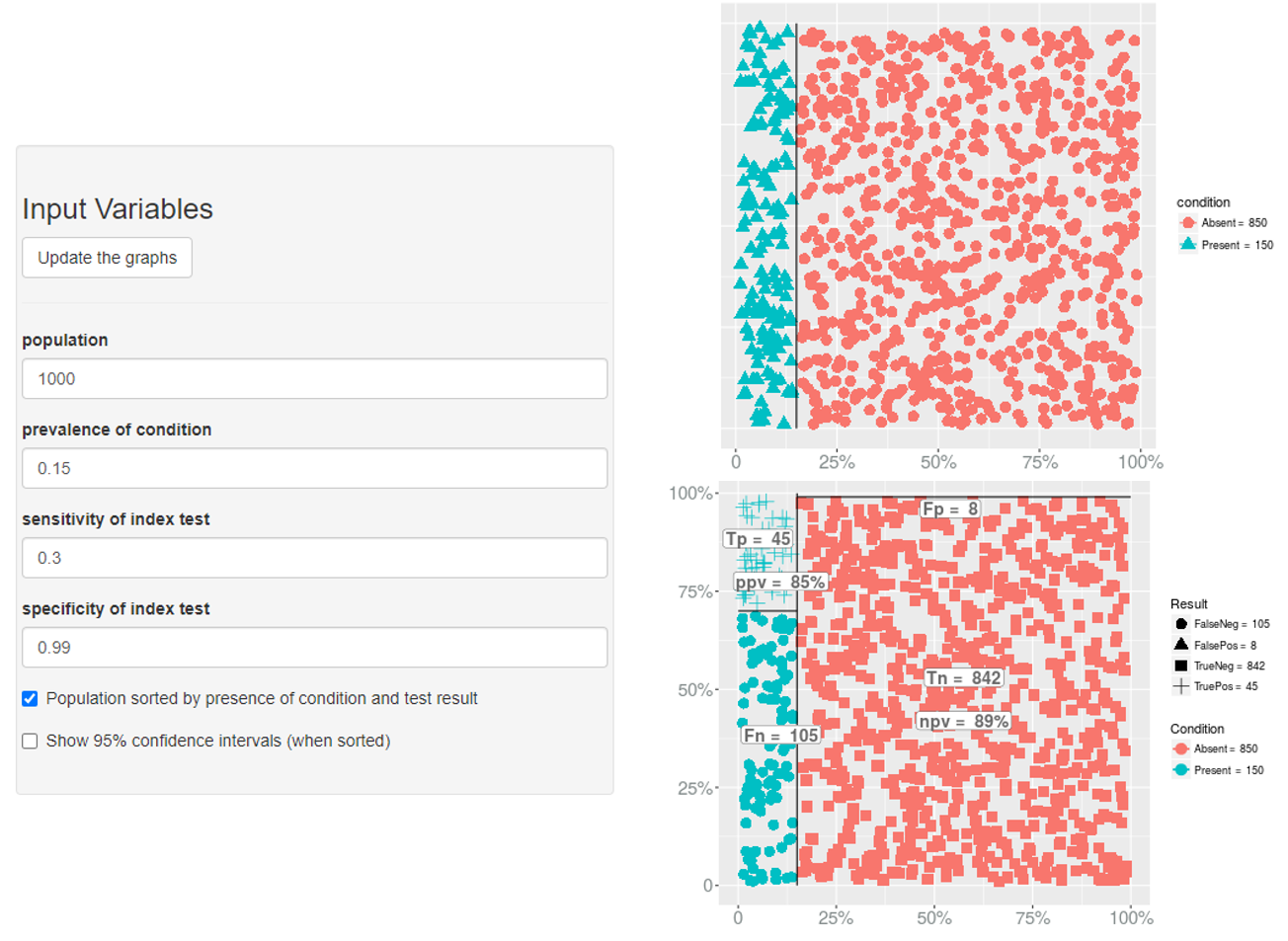

PPV and NPV are prevalence-dependent

Prevalence → PPV & NPV

- PPV?

Prevalence → PPV & NPV

- PPV?

- PPV = 90/(180+90) = 0.3333333

Prevalence → PPV & NPV

- PPV?

- PPV = 90/(180+90) = 0.3333333

- NPV?

Prevalence → PPV & NPV

- PPV?

- PPV = 90/(180+90) = 0.3333333

- NPV?

- NPV = 720/(720+10) = 0.9863014

Prevalence → PPV & NPV

Prevalence → Sensitivity

Prevalence → Specificity

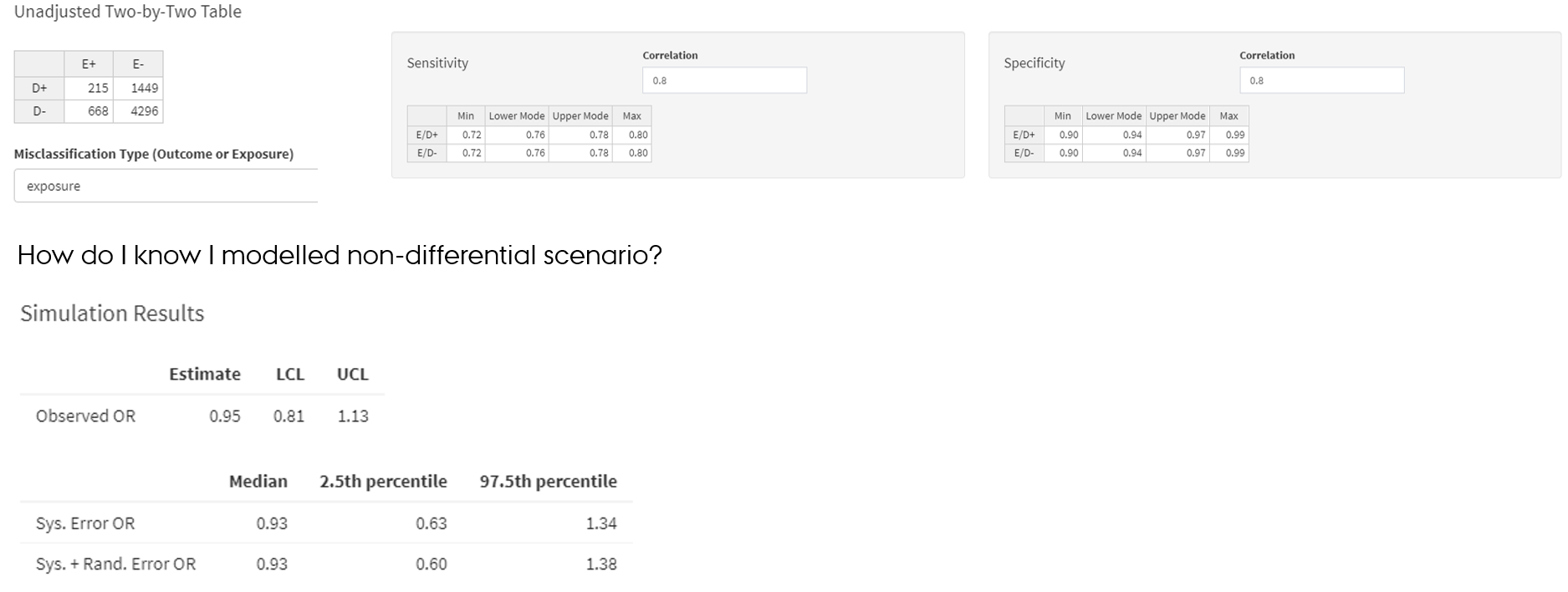

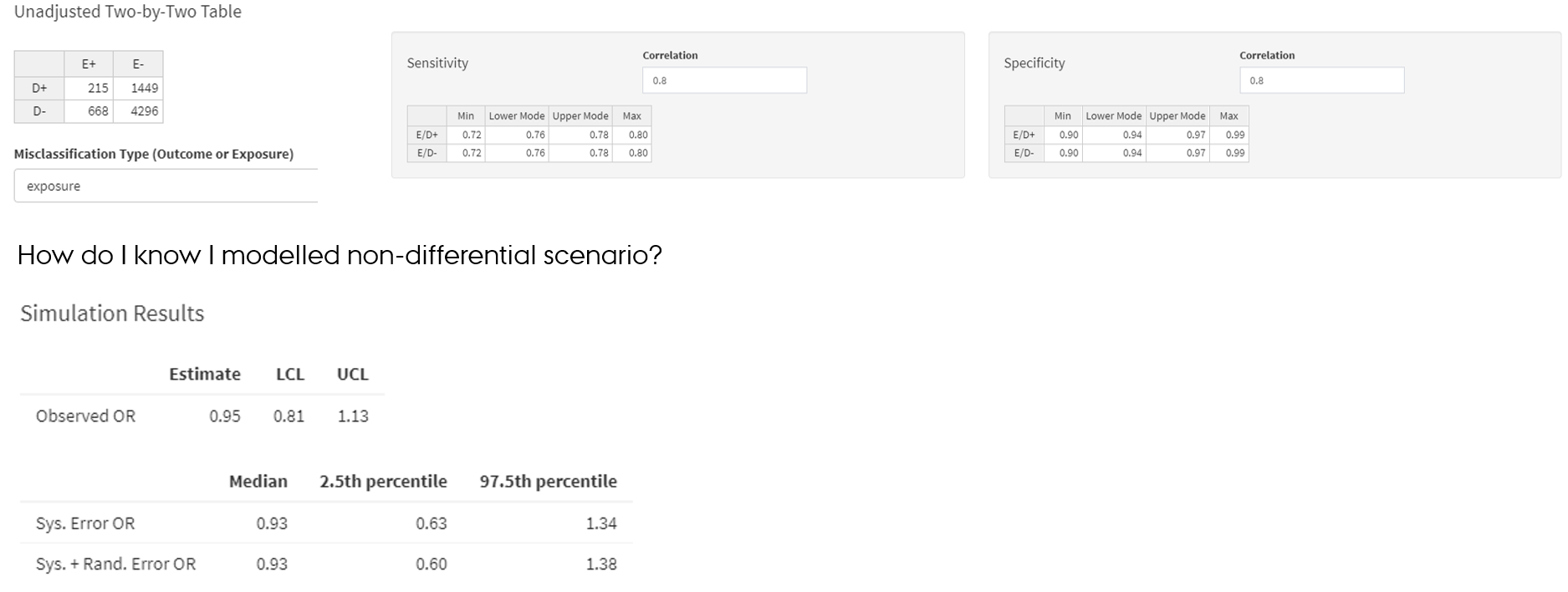

Non-differential misclassification of the exposure

Non-differential misclassification of the exposure

- SE and SP parameters of the exposure are same among outcome+ and outcome- → exposure is misclassified non-differentially in regard to the outcome

https://graeme-pmott.shinyapps.io/prob_bias_analysis/

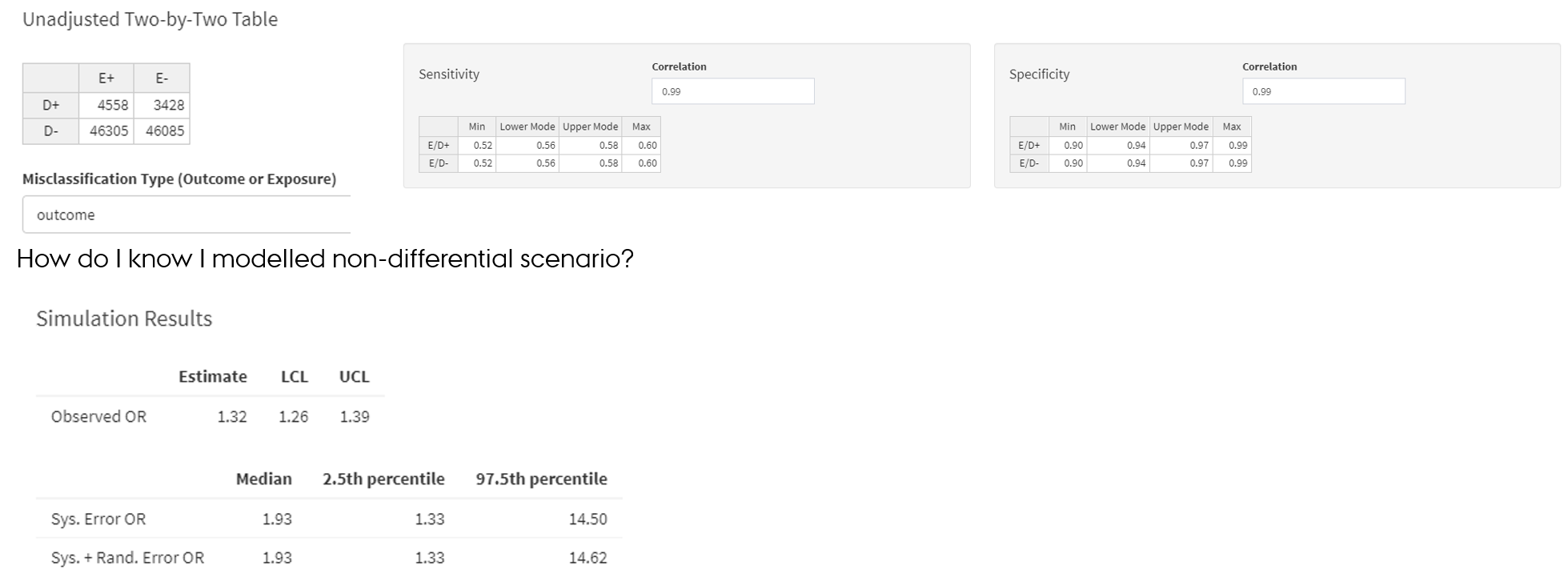

Non-differential misclassification of the outcome

- Lash TL, Fox MP, Fink AK. Applying Quantitative Bias Analysis to Epidemiologic Data. Springer. 2009; Chapter 6 De et al., 1998

- https://graeme-pmott.shinyapps.io/prob_bias_analysis/